AND THE JAPANESE HOUSE & GARDEN

JUNZO YOSHIMURA

A History and Cultural-Architectural Analysis

Feature photo from here

Originally submitted as part of the curriculum at the Community College of Philadelphia | April 8, 2024

Presented at the 31st Japan Studies Association conference, Honolulu, HI | January 2025 | Program

1st Prize Winner, Best Student Paper | Presented at the 32nd Asian Studies Development Program conference, Washington, DC | March 2025 | Program

Winner, Outstanding Presentation | Presented at the 16th Greater Philadelphia Asian Studies Consortium conference, Collegeville, PA | April 2025 | Program

View the accompanying Sway presentation here

Abstract

In Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, there is a serene Japanese house and garden. Even if you live in town, you may not even know of its existence. You may have seen the blossoming cherry trees on your friend’s Instagram account, but you aren’t quite sure where they are. This paper won’t help you locate Shōfūsō on a map, but rather, it will introduce to you the rich history of how it came to be. From 1876 and before to today and beyond. It will also reveal just how what looks to be a seventeenth century tea house from the Far East captured the imaginations of Modernist architects, and continues to enthrall contemporary designers. After reading, I hope that you visit the little Japanese house in Fairmount Park, and that you might feel the lives of those it touched, and see the home as was intended by its creators.

1st Prize,

Best Student Paper

Presented at the East-West Center’s Asian Studies Development Program 32nd National Convention in Washington, D.C., March 2025

Outstanding Presentation

Presented at the Greater Philadelphia Asian Studies Consortium Conference at Ursinus College, Collegeville, PA, April 2025

-

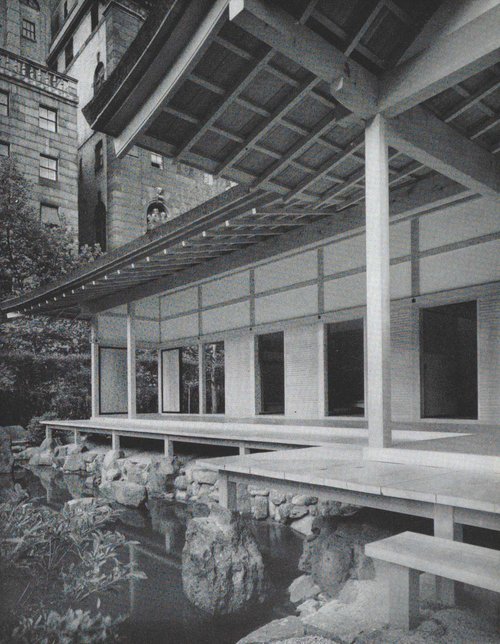

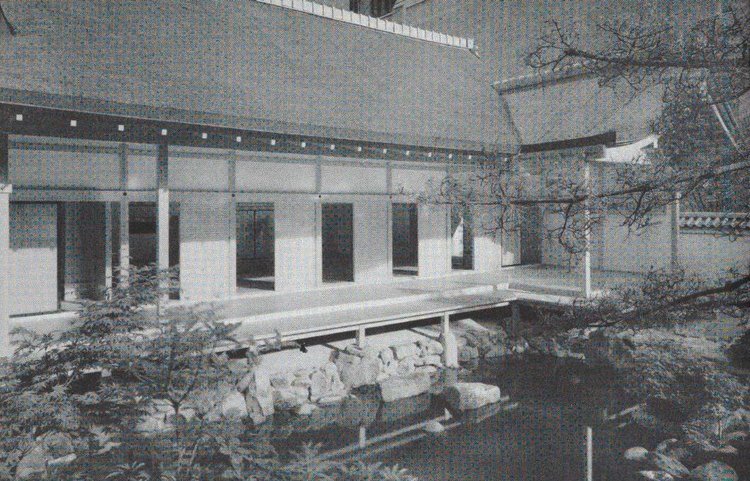

View of the installation at MoMA (MoMA, 1956)

Introduction

Deep within Fairmount Park lies a testament to the long-lasting international friendship between Japan and the city of Philadelphia (JASGP, 1999, p. 1.1; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 266; RBF, 2020, 00:03:42). It comes in the form in the style of a seventeenth century shoin-zukuri Japanese house and garden, perfectly placed amongst the cherry blossoms and atop a lotus pond. From it, guests feel the “flawless harmony of natural beauty and human creation” (Lee, 2009, para. 1). A gift from the Japanese government, Shōfūsō has a storied history beginning well before its construction in Nagoya, its exhibit in New York City, and finally, its move to Philadelphia. Today, it is “recognized as one of the most significant sites in the United States,” not just because of its beauty and serenity, but because of its architectural significance and profound implications to Modern and contemporary architecture (Whitaker, 2022, p. 27). While today, it provides an “authentic re-creation” of Edo period (1603-1868) Japanese architecture, feeling as if it were delivered straight from Kyōto (Scott, 2020, para. 18; Mikati, 2022, para. 11), it is also a testament to the “art, craftsmanship, and concepts” (Polyakov, 2021, p. 9-10) of traditional tenets that transcend time and space to influence masterful twentieth and twenty-first century homes throughout the West. Like Philadelphia itself, it faced a turbulent history, but with the attention and care from people who love the home, it continues to thrive as a cultural ambassador to Japan and to the lessons to be taken from traditional design. This is merely an introduction to Shōfūsō, as it will speak to you itself upon your first visit, and every visit thereafter.

Prior to detailing its storied past and looking to its bright future, I graciously extend a note of thanks to all of those who have fought for Shōfūsō’s survival, and continue to care deeply about the little Japanese house. Particularly helpful have been the team at the Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia, who work to maintain the house and offer culturally important courses throughout the year; Mr. William Whitaker, curator and collections manager of the architectural archives at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design; and Professor Michael Stern at the Community College of Philadelphia, whose lively conversations about Shōfūsō have pushed me to dive deeper into this topic than may have been expected. Their contributions, although almost certainly unbeknownst to them, have been invaluable.

Philadelphia and Japan

Philadelphia has a lengthy and storied connection to Japan that reaches back centuries, to even before Japan once again opened its shores and ports to the West. It is a living legacy, as we shall see, but much of it is hidden away, records kept only in niche books and colorless photographs. A fascinatingly important but fairly unknown connection is the fact that Commodore Perry’s ship with which he forcibly reopened Japan to the West was built in and launched from Philadelphia’s Naval Yard, when it was still located in Southwark off Federal Street (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 19). Even before then, while Japan remained isolated, a castaway named Manjirō’s manuscript of his worldwide adventures in 1841 landed itself in the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 19). A full analysis of this international connection is presented in a collection published by the Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia (2015).

1876 Centennial Exposition

-

Photograph of the Japanese Dwelling at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia (Centennial Photographic Co., 1876)

-

Photo of the Commissioner’s Building - despite the lower title (Wescott & Hunter, 1876)

The story of Shōfūsō, however, begins just a few dozen yards away from where it sits today, with Japan’s first international showcase since its inauguration into the steadily globalizing world in 1854. The 1876 Centennial Exhibition, celebrating the United States’ one hundredth anniversary, was the “first world’s fair” held in the New World (Watanabe, 1985, para. 1; a.PMA, ongoing, para. 1). For Japan, it was the very first in which it participated fully (JASGP, 1999, p. 4.1; Bareis, 2016, para. 3), for which it sent over 7,000 crates of wares (JASGP, 1999, p. 4.1; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 44), only being bested in items sent and amount spent by Great Britain and the United States itself, respectively (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 51; JASGP, 1999, p. 4.1).

Not only did Japan send exquisite pottery, tea utensils, and fine silks for their display, they also constructed two buildings for viewers to experience: the Commissioner’s Building and the Japanese Dwelling or “Bazaar” (Bareis, 2016, para. 7), as well as planted the “first Japanese-style garden in North America” (Griffin, 2023, para. 4). Designed by S. Kanazawa of Kaga, it seems that the Dwelling “attracted crowds as it was being built” (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 45-6). According to G. Lawrences’ The Centennial Exhibition Guide (1876), the Japanese examples were “regarded as the finest piece of carpenter work ever seen in this county” (Bareis, 2016, para. 8), and the Atlantic Monthly stated that by comparison, their “clean lines and simple elegance” made everything else look “commonplace and vulgar” (Ujifusa, 2010, para. 7).

While Japan had hoped to impress the world with its newfound industrial might, Americans were more taken by the exotic expression of traditional art and architecture (JASGP, 1999, p. 4.1; Ujifusa, 2010, para. 6; Bareis, 2016, para. 6). Prior to the Centennial, the western world knew very little of isolated Japan, only from what was very recently published in books and tabloids (Bareis, 2016, para. 9), so this demonstration captured them completely. By the end of the Centennial, even the newly-established Pennsylvania Museum (now the Philadelphia Museum of Art) started a Japanese collection, kicked off with a few purchases from the exhibit display (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 47; a.PMA, ongoing, para. 1).

Niō-Mon

-

An autochrome of the Niō-Mon in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia taken by Emil Albrecht in 1912 (Griffin, 2023)

-

A postcard-sized print of an artistic rendition (Japanese Garden and Pagoda, Fairmount Park, ca. 1930)

Nearly thirty years after the Centennial Exposition had ended and their displays deconstructed, St. Louis hosted the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in 1904 (Watanabe, 1985, para. 2; c.JASGP, n.d., para. 4; Milroy, 2016, para. 1). On display was a stunning 45-foot tall fourteenth century temple gate imported from Japan (“Nio-Mon”, 1906, para. 1; Finkel, 2015, para. 8; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 92; Milroy, 2016, para. 1; Griffin, 2023, para. 5; c.JASGP, n.d., para. 4). Two Philadelphian industrialists purchased and donated the gate to the Fairmount Park Commission (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 94; Finkel, 2015, para. 7; Griffin, 2023, para. 5). Located in the park at the site of a lotus pond, constructed between 1878 and 1894 (JASGP, 1999, p. 4.2), mistakenly believed to be the site of the Japanese exhibit during the 1876 Centennial (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 95), the Niō-Mon gate went up in Philadelphia in 1908.

Though the gate was popular for visitors, it was also a hotbed for vandals. “Almost immediately” after it was erected did vandals begin to cause damage to the half-millennia-old temple gate (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 95). Though it had seen some intensive renovations and much of its ornament had been relocated to the PMA, “no protective measures” were taken to protect the Niō-Mon, primarily because the Fairmount Park Commission would not allocate funding for it (JASGP, 1999, p. 4.2; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 95). Even Park Commissioner John Kelly thought that it may need to be “torn down” due to its neglect (Finkel, 2015, para. 10).

The Niō-Mon ultimately would not be demolished - rather, it suffered far worse a fate. On the eve of a 1955 renovation, the Niō-Mon burned to the ground in an intense flame (JASGP, 1999, p. 4.2; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 95; c.JASGP, n.d., para. 5). Historians disagree on whether it was vandalism or negligent construction workers, but the Philadelphia Fire Department discerned that it was caused by a “carelessly discarded cigarette” (Finkel, 2015, para. 11). According to Kim Andrews, the Executive Director of the Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia, the fire blazed for three devastating days (Rearick, 2012, para. 11). In publishing the news, the Philadelphia Inquirer unironically described the Niō-Mon as “one of Philadelphia’s best known and best loved landmarks” (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 92). However, its unexpected but not untimely demise would prove fortuitous for the development of our story, as on its former site now sits Shōfūsō.

Other Historic Connections

Well before the Niō-Mon met its cruel end, the international relationship remained strong since Japan’s first foray with Philadelphia during the 1876 Centennial. For the United States’ sesquicentennial in 1926, the Japanese government gifted the city 1600 flowering trees, including our popular cherry blossoms in Fairmount Park and on Kelly Drive. Ambassador Tsuneo Matsudaira noted that, “to us your city has been what its name signifies, ‘brotherly love’” (Watanabe, 1985, para. 3; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 57; 59). Likewise, Philadelphia remained enamored with all things Japanese. Like Shōfūsō, another historic example of Japanese architecture can still be seen and experienced today without leaving town. Buried in the halls of the PMA lies the pièce de résistance of its Japanese collection: Sunkaraku, or “Evanescent Joys” (or also “Momentary Leisure”), is a 1917 tea house designed by Ōgi Rodō, acquired by the Museum in 1928 (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 98-9; b.PMA, ongoing, paras. 1-3).

Upon Japan’s introduction to the rest of the world, Philadelphia and the whole of the West were captivated by its exotic art, architecture, and culture. However, according to Gattamorta & Perkins (2020), by the 1920s, this trend “reversed course” and Japan began to integrate ideas from the West back home (para. 14). One man who was particularly captured by the newly ideating Modern movement was Yoshimura Junzō, who had a long road ahead before designing Shōfūsō.

Who was Junzō Yoshimura?

-

Junzō Yoshimura, circa late 1960s to early 1970s, with his drawing for the Japan Society building (RBF, 2020)

Junzō Yoshimura (as we would call him) was born in Tokyo in 1908 (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 11). He was just a teenager when Western ideas began to infiltrate his country, and a 1923 visit to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel in Tokyo pushed him to pursue architecture. “It was the first time that I felt emotional when faced with architecture,” Mr. Yoshimura recalled. “It’s certainly the main reason I became an architect” (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 15). Just a few years later, as a young adult, he enrolled in the Tokyo Arts College (Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō, now the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music) to obtain a degree in architecture (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2; Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 16; Whitaker, 2022, p. 34).

Experience with Antonin and Noémi Raymond

-

Antonin and Noémi Raymond’s Tokyo office staff, ca. 1935. Yoshimura stands next to Mrs. Raymond with hands on his shoulders. George Nakashima smolders in the center of the back row (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020)

-

Yoshimura kicks back at Raymond Farm in New Hope, Pennsylvania (Whitaker, 2022)

While still a student, in 1928 Junzō began working in the Tokyo office of Antonin and Noémi Raymond (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 16). Incidentally, the Raymonds had first arrived in Japan to work under Wright for the Imperial Hotel, and decided to stay following the 1923 Kanto earthquake and subsequent great fire in Tokyo (JASGP, 2021, 00:27:35; Whitaker, 2022, p. 35-7). Upon his graduation in 1931, Junzō began working full time with the Raymonds (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2; Whitaker, 2022, p. 35-7). Alongside Yoshimura in the office was another young architect, George Nakashima, also dearly beloved to Philadelphia (Hironaka, 2020, 00:04:47; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 22).

As a young architect, Yoshimura spent more than a decade working under the Raymonds. Antonin clearly had taken a liking to Junzō, recalling “what was most sympathetic to me was his knowledge of and interest in Japanese arts and architecture” (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 17), as well as his “deep respect for… the craft tradition of Japan” (JASGP, 2020, 00:02:54). Yoshimura was also “keen on engaging with the international context” with the firm (JASGP, 2021, 00:33:15), so by the turn of 1940, the Raymonds invited Junzō (and Nakashima) to join them at their office in New Hope, Pennsylvania.

In Tokyo and then in New Hope, Yoshimura and Nakashima became “quite friendly,” according to Nakashima’s 1981 book, Soul of the Tree. To Nakashima, Junzō “knew so well the elegance of power and simplicity, the beauty of proper materials in building, the delicacy of unfinished wood… He knew these things well in both the time-honored Japanese design and in the free modern concepts, and he passed them on to me,” he writes. “I owe so much to Junzō and his deep understanding” (RBF, 2020, 00:09:44). In the gentle calm of New Hope, Junzō “discovered a kind of ‘primitive hut’ that would become an important source for his… creativity” (Whitaker, 2022, p. 40). It was here, according to Tadashi Oshima, that Yoshimura and Nakashima experienced “being connected to the land appreciating art and having a holistic view as the basis of this creative process” (Hironaka, 2020, 00:04:47). Yoshimura’s “profound connection with nature” combined with this seemingly carefree life in Pennsylvania would result in “a perfect balance between traditional Japanese construction methods and the canons of modern western composition” (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 6; 16).

Unfortunately, the idyllic landscape and lifestyle that Yoshimura experienced in the United States could last no longer. Tensions were boiling over between Imperial Japan and the United States, exacerbated by a U.S.-imposed blockade of the island nation. Just eighteen months after he arrived, Junzō was compelled to leave the home he purchased next to Raymond Farm (Seymour, 2022, para. 14) and to return to Japan. In a letter to their Tokyo office, Noémi Raymond lamented that “art had ceased to exist everywhere” (RBF, 2020, 00:20:54). “Many things are going through my mind right now, like a dream,” Yoshimura wrote from the last ship leaving San Francisco. “And every image ends at peaceful life of New Hope” (RBF, 2020, 00:21:29). George Nakashima, on the other hand, like so many others, was incarcerated in an Japanese internment camp in Idaho, if only for a little while, where he would learn woodworking (Seymour, 2022, para. 15; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 22).

Other Works

Upon returning to Japan on the eve of an official declaration of war between Japan and the United States, Yoshimura established his own practice in Tokyo and became a professor at his alma mater a decade later (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2). Over his career, he designed and built over 150 private dwellings, feeling a “social obligation” as an architect to the family (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, paras. 21; 29). “As an architect,” Yoshimura recalled, “I am gladdened when I have completed a building and can see people having a good life inside it… Being able to sense that the family enjoys their daily life; isn’t that the most rewarding moment for an architect?” (Whitaker & Yokoyama, 2022, p. 9). Though, he also worked on quite a few public spaces. According to Whitaker (2022), his “best-known work… is the Japan House, the home of the Japan Society in New York” next to the United Nations (p. 51). He was finalizing plans for the International House of Japan in Tokyo (1952-55), an attempted “transition into the modern era” for Japan when he was approached to build an Exhibition House for MoMA (Barr, 2018, para. 2; 5).

Aside from Shōfūsō and the Japan House in New York, Yoshimura has a handful of other buildings in the United States, but he mostly worked in Japan. Despite his legacy remaining “largely invisible in the United States” (RBF, 2020, 00:08:42), he is known as “the most classical among contemporary Japanese architects” (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 1). His experience with Modernists Antonin and Noémi Raymond, as well as his dedication to traditional Japanese construction allowed Yoshimura to see the world and life with “a new vision” (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 17), one that would meld perfectly the concepts of classicism and innovation, and one that would lend perfectly to the development of Shōfūsō.

Exhibition # 559

-

Yoshumura’s sketch of Shōfūsō (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020)

-

An aerial view of Exhibit #559 at MoMA in New York City (Drexler, 1955)

-

View from the gate (Drexler, 1955)

-

View of the pool and garden from the veranda (Stoller, 1954)

In New York, the Museum of Modern Art was readying for its third installation of its House in the Garden series. To be set in its Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden (now the Education and Research Building at MoMA), this exhibit featured full-scale examples of contemporary architecture. Previously, MoMA had showcased plans and drawings, and started featuring small models in 1944. In 1949, the first full home, designed by Marcel Breuer, was built in the garden as MoMA wished to instill a “direct experience of architectural space and materials.” A year later, Gregory Ain and a team from Women’s Home Companion put up the second exhibition house (Whitaker, 2022, p. 28-30). Following the success of two Modern American homes, the executors at MoMA decided to turn elsewhere for their third installation. With the backdrop of the Korean and Cold Wars, many in the U.S. “sought to consolidate relationships” with the Far East once again (Barr, 2018, para. 3). Newly-instated Curator of Architecture at MoMA Arthur Drexler, following a trip to Japan and a long search committee process, ultimately “made the decision to build an example of classical Japanese architecture” and selected Yoshimura as its architect (Whitaker, 2022, p. 28).

Despite the two prior examples being strictly Western Modernist expressions of residences, Drexler and Yoshimura recognized “the unique relevance” the Japanese style and construction had to Modern architecture, which could not only teach pertinent lessons to Western designers, but also help them “begin to understand Japanese culture as a whole” (Peterson et al., 1955, 00:01:55; Scott, 2020, para. 23). According to Curator Drexler (1955), he chose this “to illustrate some of the characteristics of buildings considered by the Japanese to be masterpieces, and considered by Western architects to be of continuing relevance to our own building activities… [with] a more disciplined esthetic [sic] and a wider technical range” (p. 262). Likewise, Yoshimura was an easy choice. His “deep knowledge and understanding” of traditional Japanese architecture, as well as his international experience with the Raymonds, allowed him to design the exhibition house “with America in mind” (Whitaker, 2022, p. 27).

Inspiration for Shōfūsō

-

Kōjō’in reception hall at the Onjōji Temple in Ōtsu City, outside Kyoto. Its similarities to Shōfūsō are striking (Kojoin Reception Hall, 2019)

-

Kōjō’in garden behind the reception hall (Kojoin Garden, 2019)

Kyōto’s famed history played an important role in the development of Shōfūsō. The city and its surrounding area hosts “more than 2,000 Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines” (Oi, 2015, para. 3). When Drexler and his entourage visited to scope out precedents for his exhibition house, he was struck by the Kōjō’in reception hall at the Onjōji Temple in Ōtsu City, the “pure light compound,” just outside Kyōto (JASGP, 1999, p.2.2; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 262; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 12; 15). Other sites he visited, such as Nagoya Castle, Katsura Rikyū and Shugakuin Rikyū palaces, and Ginkaku-ji and Ryōan-ji temples all melded together to add detail to Shōfūsō, and its sukiya (teahouse) is based on the Daitoku-ji sukiya in Kyōto (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2). However, Kōjō’in was perfect for Drexler, as he saw the temple as “most representative of the traditional Japanese architecture” (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2).

Curiously, at the tail end of World War II, Kyōto was the number one target for the atomic bomb due to its cultural and intellectual importance as well as its population size. However, it was the insistence of one man, Secretary of War Henry Stimson, that spared the city both because he had visited in the 1920s (though decidedly not for a honeymoon) and “knew it was a great center of Japanese culture.” He argued that “such a wanton act” in destroying the cultural center of the country “might make [reconciliation] impossible” between Japan and the United States (Wellerstein, 2020, p. 39; 42). Shōfūsō could have looked very different - or indeed, never have existed - had Stimson wavered in his position to protect the city.

Since Kyōto ultimately was spared, the team from MoMA had exemplary pieces to discover inspiration. Like Kōjō’in, Shōfūsō is an example of Shoin-zukuri style architecture. Perhaps not coincidentally, this was square within Yoshimura’s wheelhouse: “If you want to study Japanese architecture…. begin by studying the shoin style,” Yoshimura noted (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 2). Named for its shoin (desk) in the main room, these homes were designed for those who may have required such a writing table: scholars, government officials, or priests (MoMA, 1954, para. 9). Despite not being the vernacular example of Japanese residences, Drexler posited that shoin “called for a more disciplined esthetic [sic] and a wider technical range” than farmhouses or tea rooms (Drexler, 1955, p. 262; Whitaker, 2022, p. 33-4).

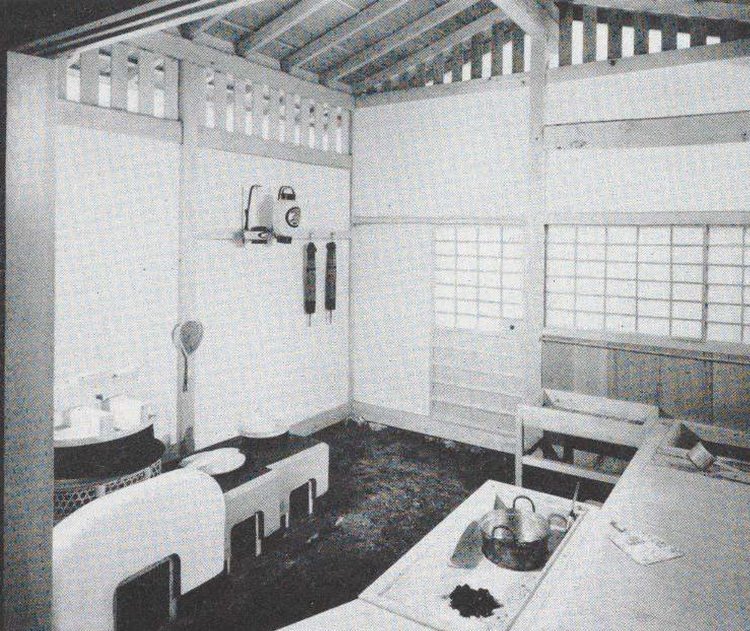

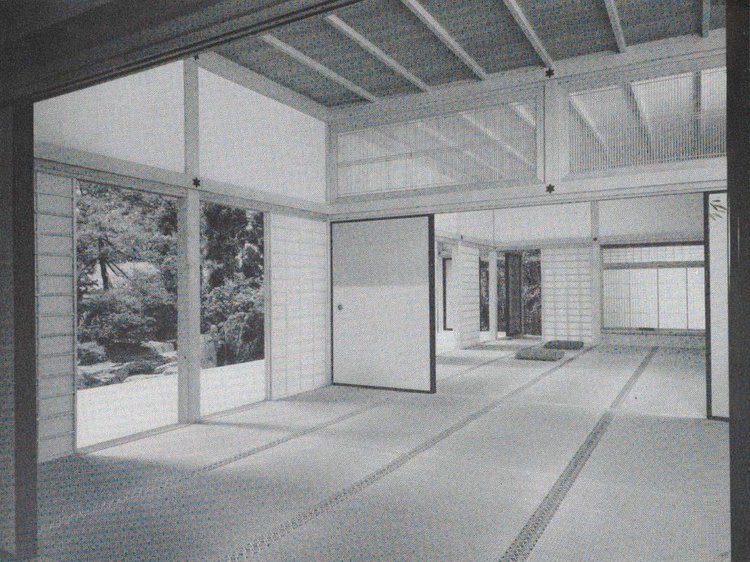

As can be seen now at the house in Philadelphia, shoin-zukuri features an asymmetrical floor plan, fusuma (interior sliding doors), amado (sliding shutters), shoji (exterior sliding doors), tatami (rice straw mats). Further, according to the Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia, charged with operating Shōfūsō, there are four basic elements of shoin-zukuri: the tsukeshoin (built-in desk), tokonoma (sacred shrine), chigaidana (staggered shelves), and chidaigamae (decorative doors). In Japan, it’s uncommon that a shoin style home would have each element, but “Shofuso has all four” (JASGP, 1999, p. 9.3). In the end, Shōfūsō melds together three Japanese styles: shoin-zukuri for the main form, minka style with its distinct earthen-floor kitchen, and a sukiya style teahouse, embracing the “design philosophy of wabi-sabi,” or “less is more” (Griffin, 2023, para. 8).

Although Shōfūsō was a novel building constructed specifically for the exhibition, it is an honest representation of classical Japanese architecture as it would have appeared in the seventeenth century (Drexler, 1955, p. 263). According to Drexler’s first statement of objectives for the exhibit, they made “no concessions to modern lighting or plumbing, or substitutions of glass for paper” (Whitaker, 2022, p. 32). Though inspired by these Kyōto examples, and being especially similar to Kōjō’in, Shōfūsō is not a carbon-copy. Instead, Yoshimura, either consciously or subconsciously, practiced utsushi: “homage to spirited inspiration” or “inspired renditions:” “It [does] not simply copy the form of the inspiration,” details Yukie Yokoyama, Associate Director of Exhibits and Programs at JASGP. “But rather [is]…. building creative communication with them, softly expanding on foundation and creating an interrelated family [of] masterpieces” (Polyakov, 2021, p. 10; JASGP, 2021, 00:08:49).

Breaking Ground

-

Yoshimura stands in the center of Shōfūsō’s many crates, as published in Life Magazine (RBF, 2020)

-

Some of the construction team in New York (Griffin, 2023)

As important to Shōfūsō’s creation as Drexler and Yoshimura were John III and Blanchette Rockefeller. In fact, since the end of World War II, the Rockefellers were integral in not only negotiating the antebellum peace treaty, but also in supporting “cultural relations and intellectual exchange programs” (RBF, 2020, 00:25:18; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 12-3). As the President of the Japan Society in New York, John III was an “influential advocate” for amnesty between the U.S. and Japan (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2). Thus, the Rockefellers were even pivotal in recruiting Yoshimura for the exhibit, as they had worked with both him and Antonin Raymond for a teahouse in Kykuit, New York (RBF, 2020, 00:25:51; Whitaker, 2022, p. 31; 48). Because of this eminent couple, the Japanese government gifted the Japanese exhibit house to the United States as a “symbolic gesture” of their renewed relationship. Though the gift was generous, it was Blanchette who personally granted funds when the budget got too tight (Lee, 2009, para. 2; Whitaker, 2022, p. 49).

Likewise, Drexler played an indispensable role as an intermediary between Yoshimura and the Rockefellers and as a compass towards the goal of the showcase: “to share the art, craftsmanship, and concepts of Japanese residential design in architecture and gardening” (Polyakov, 2021, p. 9-10). The high standards and fine material extolled by Japanese construction did not come cheaply. In many ways, according to Whitaker (2022), Drexler’s “most significant contribution” was to, essentially, disregard the budget. Yoshimura, more than two decades into practice, was keenly cost-conscious, moving as far as to significantly rework his plans. For example, when confronted with Yoshimura’s alterations to minimize the cost of the garden, Drexler exclaimed, “I… want the water and plants!” There was nothing that would deter him from achieving a “truly impressive” house. “Dear Junzō,” Drexler reassured his frugal architect, “good architecture any place, any time, is expensive.” Mrs. Rockefeller signed the cheque (p. 47-9).

And expensive Shōfūsō would be. Yoshimura had no such qualms with the cost of detailing the house as he did with the garden. “With design alone,” Junzō noted, “not even Picasso can do a painting… It’s exactly the same with me as an architect” (Time Magazine, 1965, para. 4). Take for example the hinoki bark roof. Taken with special permission from the national Japanese cypress forests, Yoshimura integrated “hundreds - maybe thousands of pieces” of the “expensive and elegant” wood (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.3; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 263; Carroll, 2017, para. 2). However, this is not entirely unordinary for Japanese homemaking. According to Peterson et al. (1955), “the idea that a house is a roof is not an unusual one, but the Japanese have developed it to an unusual extent… When they speak of the beauty of a building… they think at once of the… texture of the roof” (00:05:05). Though expertly crafted and unspeakably beautiful, hinoki has a short life span, needing to be replaced every twenty to twenty-five years (JASGP, 1999, p. 8.1). Thus, as we shall later see, it remains costly.

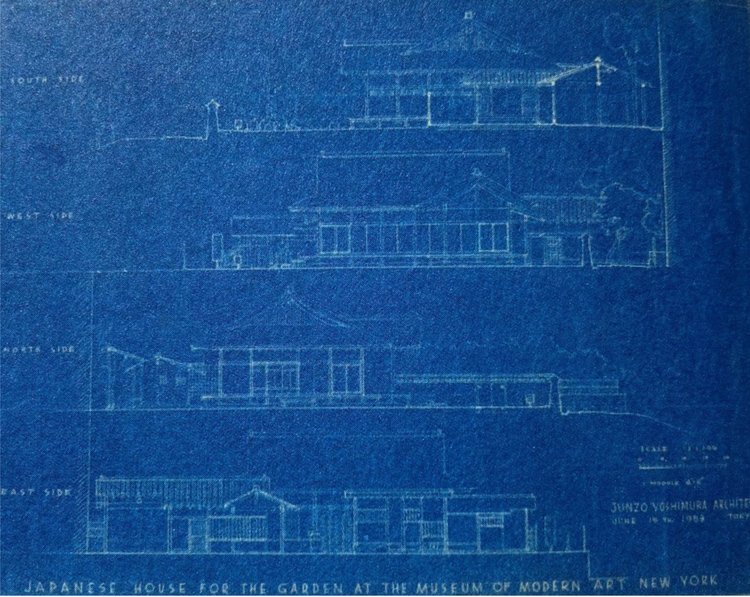

-

Japanese Exhibition House plan as of August 15, 1953 (Whitaker, 2022)

-

Elevations as of June 15, 1953 (Whitaker, 2022)

While Shōfūsō was a solo project for Yoshimura, his time with the Raymonds and Nakashima echoes throughout the house. According to Whitaker (2022), “it is clear that Yoshimura sought out… advice” from Antonin and Noémi (p. 48): “You can see this friendship [between Yoshimura, Nakashima and the Raymonds] in the house’s design,” says Yuka Yokoyama, Curator and Program Manager for Shōfūsō (Seymour, 2022, para. 8). Construction, on the other hand, would come down to the wire. Yoshimura and his crew of some of the “best” artisans in Japan (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 13) were busy building the house at its original home in Nagoya. For the start of the 1954 exhibition, it still had to make its way across the Pacific, then all the way to New York. Carpenters and gardeners and detailers were spread so thin that even Junzō’s wife, Takiko, had to help (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.5; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 264). Finally, the house was ready to be shipped. In all, nearly 700 crates sailed from Japan to the United States, including 23 tons of stones hand-selected from the Takayama Mountains, carefully wrapped to preserve the moss growing on them (Drexler, 1955, p. 262; JASGP, 1999, p. 2.3; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 262-3; Whitaker, 2022, p. 49-50). Yoshimura packed up himself, and set sail for the U.S. shortly after.

-

Tansai Sano (seated) and colleagues at the jōtōshiki pole raising ceremony (Whitaker, 2022)

-

Yoshimura at the site under construction (Hironaka, 2020)

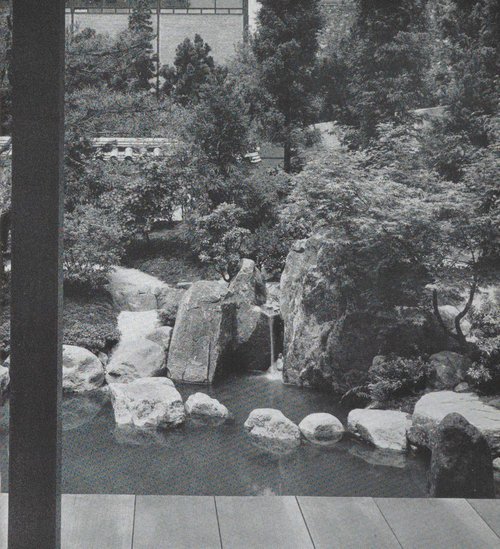

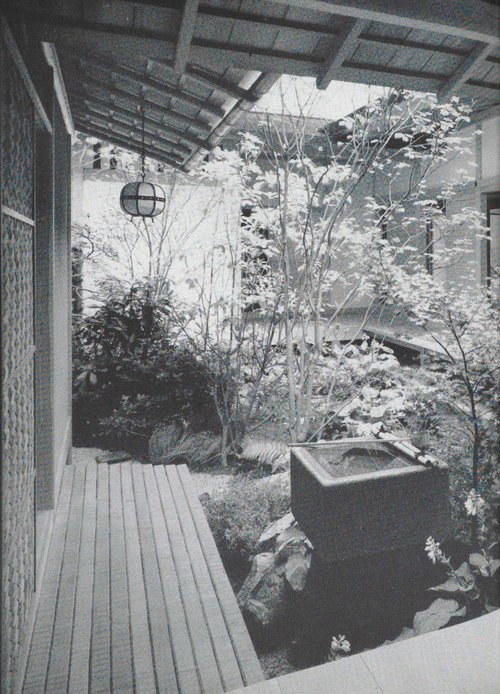

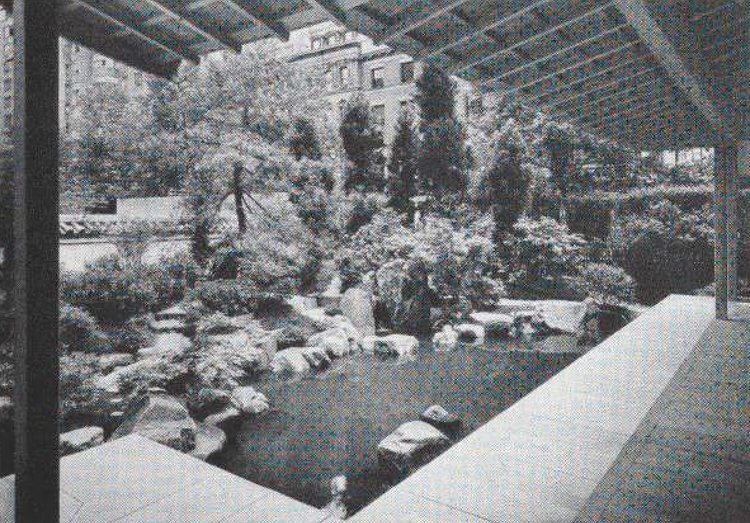

By Spring of 1954, the crates finally arrived in New York. The start of construction at MoMA was marked with a jōtōshiki (or mune age), a pole-raising ceremony, officiated by a buddhist monk to wish good fortune on the house (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.4; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 263; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 13). It was then that Shōfūsō got its name, meaning “pine breeze villa,” likely given by Drexler (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.4). The exhibition construction went underway. According to Whitaker, it was “fairly rare” for an architect to work outside their home country at that time (Hironaka, 2020, 00:09:41), but Yoshimura felt welcome in the United States. While the house just needed reconstruction, the garden required creative expertise. Yoshimura himself led a fundraising effort to hire Tansai Sano, a “famed” seventh-generation landscape gardener. For Shōfūsō, Sano visited traditional gardens in Nara and Kyōto, perfectly evoking “a deep mountain scenery akin” to Kōjō’in (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.2; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p.13; 18 ; Whitaker, 2022, p. 49-50). According to Sandi Polyakov (2021), the head gardener at Shōfūsō today, like Yoshimura’s house, “Sano’s MoMA garden evolved its site-specific personality” (p. 10).

Shōfūsō opened to the public on June 20, 1954 to an astounding 1,356 viewers (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.6; Whitaker, 2022, p. 50). The publicity, according to Chance & Toda (2015) certainly made quite the buzz, and even during its construction it had a “great… impact” on New Yorkers (p. 263). Drexler was equally as pleased, saying the exhibit surpassed his “highest expectations,” noting that Yoshimura’s house and Sano’s garden “created an illusion so perfect that one almost believes oneself to be in Kyōto” (Whitaker, 2022, p. 50-1). It may be difficult now to imagine a quiet Japanese house and garden in bustling Midtown Manhattan, but Yoshimura “consciously juxtaposed” the towering skyscrapers with his little abode, creating an “unexpected dialogue” in its original American home (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 19; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 13). Yet, at ground level, Shōfūsō achieved the Japanese spirit of mono no aware, an “intimate harmony” deep within the heart of New York City (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 38).

-

After the jōtōshiki. Arthur Drexler is on the far left and Junzō Yoshimura on the far right (Sunami, 1954)

-

Visitors at Shōfūsō for its opening. Note the paper slippers on their feet for the delicate tatami (Sunami, 1954)

By the end of its first season, closing in October that year, the house had been viewed by 121,187 “slipper shod” visitors, “about three times more” than the previous two exhibition houses, although it seems many had come on multiple occasions. Life Magazine would call it “the city’s most popular summer rendezvous”(JASGP, 1999, p. 2.6; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 11-2). For its second season in 1955, the garden was expanded by 400 square feet and added various new plantings. By its close in October 1955, the house had nearly doubled its visitation to a total of 223,124 people over its two years in New York (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.6-7). With that, its time in the Big Apple came to an end.

-

“Shin-ichi-Yuzie who sang and played the Koto” at an event at MoMA’s House in the Garden, May 26, 1955 (Kramer, 1955)

Move to Philadelphia

-

View of Shōfūsō from across its koi pond (Williams, 2022)

-

An aerial view of Fairmount Park with Memorial Hall and the Philadelphia skyline behind (Hironaka, 2020)

Though the MoMA exhibit had closed, the Japanese house and garden lives on. As a gift of friendship, the Japanese government stipulated that Shōfūsō be relocated, preferably on the east coast due to its limited Asian representation. Very nearly did the house move to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York or next to the Japanese Embassy in Washington, D.C., but could not compromise on any deal for budgetary or logistical reasons (JASGP, 1999, p. 3.1; Whitaker, 2022, p. 30). After eight months without a decision, Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park was finally chosen as Shōfūsō’s new permanent home, allegedly with the help of Mayor Richardson Dilworth’s friendly relationship with the Rockefellers (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 263; RBF, 2020, 01:03:48).

Fairmount Park proved to be an ideal landscape for the Japanese house. The New York Times report lauded the selection due to the Park’s “outstanding record of maintaining and displaying historic houses” - likely thinking of Memorial Hall and various others, and not of the recently scorched Niō-Mon - and that it would make a “much more handsome setting” than downtown New York (JASGP, 1999, p. 5.2; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 264; Whitaker, 2022, p. 51). In Philadelphia, it was thought “appropriate” to be a “continuation of a Japanese tradition” in the Park (JASGP, 1999, p. 3.1). Once again, Shōfūsō had the opportunity to achieve utsushi: a spirited homage to its predecessors from the Centennial and Louisiana Purchase exhibitions.

Shōfūsō in Philadelphia

-

Women in kimono at the opening of Shōfūsō in Philadelphia in 1958 (Griffin, 2023)

-

The facade that same year (Shofuso, 2018)

Similarly, Yoshimura and Sano were equally excited about the prospect of a larger, more vibrant site. To the Japanese, the efficacy of shoin-zukuri “hinges on a successful relationship with its surrounding natural environment” (JASGP, 1999, p. 2.5). Together, they saw this move as “a unique opportunity to forge an even more striking house-and-garden relationship” (Polyakov, 2021, p. 10). Dwarfing the size of its home in MoMA, Fairmount Park offered a site seven times larger (Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 17). Working with local landscape architect and his former student David Engel, Sano integrated the existing lotus pond and temple garden into his designs. Like the architect combined three different styles into the house, Sano synthesized multiple forms into his garden. Today, the garden is composed of three distinct areas: its tsukiyama (hill and pond garden), roji (a garden which surrounds the tea house), and tsubo-niwa (an urban courtyard garden) (Gorichanaz, 2016, p. 4; “Philadelphia: America’s Garden Capital,” n.d., para. 2). Unfortunately, Sano was unable to finish his work in Philadelphia due to budgetary constraints, and Engel was eventually forced out as well. Thus, the garden was ultimately never completed as per the plans (Polyakov, 2021, p. 10-1). The semi-finished garden at the time of its Philadelphian opening foreshadowed a continuation of the issues exacerbated by the Fairmount Park Commission previously faced by the Niō-Mon.

Regardless of the state of the garden, Shōfūsō was officially opened to the Philadelphia public on October 18, 1958, just about exactly three years after it had closed at MoMA (JASGP, 1999, p. 3.3; Whitaker, 2022, p. 27; c.JASGP, n.d., para. 5). Under control by the Commission, their budgetary allocation, understandably, had not changed in the three short years since the abrupt decimation of the temple gate. As such, for the first few seasons, visitors were restricted from entering the house because the Commission could not afford to maintain the delicate tatami floor (JASGP, 1999, p. 5.1; Griffin, 2023, para. 10). Despite this, Shōfūsō was an immediate hit with Philadelphians. The Evening Bulletin reported that in the three and a half years since opening, 49,754 people had visited. While this does not quite compare to its popularity in New York, its Philadelphia attendance “had surpassed the Niomon [sic] in popularity” (JASGP, 1999, p. 3.3). Under the Commission, however, Japanese-Philadelphians were hired to give tours clad in kimonos, becoming a twisted “fetishized art installation” within an “exotic backdrop for a non-Japanese audience” (Griffin, 2023, para. 11). Perhaps the reverence visitors had for the Japanese exhibit at the Centennial, faced with the loss of the Niō-Mon, never evolved into respect.

Though home to a completely new installation, the unfortunate patterns that plagued the temple gate began to affect Shōfūsō. The house faced “especially ruthless” vandalism throughout the late 1960s and 70s. The rice paper shoji screens were torn through, what little ornament inside the house was destroyed, and in one particularly heinous intrusion, a small fire was set inside (JASGP, 1999, p. 5.2; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 18; Griffin, 2023, para. 12). Just as before, the Fairmount Park Commission could not provide adequate funding to maintain nor protect the house. After these many break-ins, all the Commission could afford to allocate was meager funds for a chain-link fence (JASGP, 1999, p. 6.3; 7). Conditions worsened until the Japanese government threatened to repossess Shōfūsō in 1974. With the rapidly approaching 1976 Bicentennial celebration ahead, the Commission finally entered negotiations for a renovation of the house. However, the ‘76 Corporation, in charge of the Bicentennial celebration, refused to fund the restoration, “claiming that the Japanese American community in Philadelphia was too small to warrant its investment.” Thus, the Japanese government sent $500,000 to cover the costs as a two-hundredth birthday gift to the United States, and Yoshimura returned to Philadelphia to oversee the much-needed “major renovations” (JASGP, 1999, p. 6.1; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 265; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 18; Griffin, 2023, para. 12-3).

-

Evidence of vandalism in the 1960s (Griffin, 2023)

Friends of the Japanese House and Garden

Despite the gracious gift from the Japanese government, Shōfūsō and the rest of the diaspora in Philadelphia and the whole of the United States still faced a rocky road ahead. The 1980s were a raucous decade between Japan and the U.S., exacerbated by President Ronald Reagan’s neoconservative fiscal and international policies, spurring a contentious trade war between the two nations (Lindsey, 1982, para. 1-2; Tanaka, 2011, p. 50; Buscher, 2023, para. 7). Japanese Americans were once again caught in the crossfire, facing “racism and discrimination” due to the rising “anti-Japanese hate,” making tensions, according to the CEO of Sony at the time, “appear to have gotten as bad as they were on the eve of World War II” (Lindsey, 1982, para. 6; 10; Buscher, 2023, para. 7). One Philadelphian, often faced with interrogation of her loyalties, rather, “embraced” her Japanese heritage and “the arts and culture of her Japanese immigrant parents” (Buscher, 2023, para. 5).

-

Dr. Mary Watanabe, first President of the Friends of the Japanese House and Garden, outside Shōfūsō in 1984 (Buscher, 2023)

-

Dr. Watanabe at a Japanese folk fair in 1989 (Buscher, 2023)

Dr. Mary Ishimoto Watanabe, too, was interred as a young woman during the Second World War. After the war’s end, and the entry into the atomic age, she became the first Asian American to graduate with a doctorate from Harvard University’s biology program (Buscher, 2023, para. 1-3). She was a Nisei, a second-generation Japanese American (as opposed to an Issei, a Japanese immigrant, of whom she published as part of an exhibit at the Baluch Institute; Watanabe, 1985) (JASGP, 2023, para. 1), and again was facing discrimination in her homeland. Moved to counter the rising anti-Japanese sentiments, together with members of the Japanese American Citizens League, she led the effort to steward Shōfūsō, up to which time had been largely ignored by the Fairmount Park Commission. In December of 1981, the group established the Friends of the Japanese House and Garden (FJHG), a 501(c) nonprofit, to manage and maintain Shōfűsō (JASGP, 1999, p. 7; Griffin, 2023, para. 15; c.JASGP, n.d., para. 6). According to Buscher (2023), Dr. Watanabe was never officially granted the title of President or Director, but she certainly acted as such (para. 6).

Dr. Watanabe’s main goal was ignited by her experiences in unjustifiable incarceration and in the current anti-Japanese climate. The Friends group advocated tirelessly for the Redress Movement to compel the United States government to formally apologize for Japanese internment, as well as “participated in the multiracial coalition-building within the larger civil rights movement” (JASGP, 2023, para. 2). With Shōfūsō, they worked to “recontextualize [the Japanese house] as one for the Japanese and Japanese American community” as a “convening space” and “cultural educator” to reshape Americans’ view of the Japanese (Lee, 2009, para. 5; Griffin, 2023, para. 15; JASGP, 2023, para. 2). For the thirty years that Yoshimura’s exhibition house had been in Philadelphia, this was the first attempt to involve the Philadelphian Japanese community in a culturally significant way, and not just as an exotic backdrop for voyeuristic white Americans. Under Dr. Watanabe, the Friends group not only led successful efforts to fundraise for its maintenance, but also created “a vision of the Japanese cultural programs that are still presented there to this day” (Buscher, 2023, para. 6).

As the years went by, the FJHG stayed on its course. Throughout the late 1980s and 90s, the Friends group restored shoji screens, the Sitka spruce wood, realigned the chahitsu - the interior of the sukiya tea room - as well as added an entry gate and commissioned the redesign of the entry courtyard by Masao Kinoshita of the Urban Design Collaborative in Ohio (JASGP. 1999, p. 7). It would eventually merge with the Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia (JASGP) in 2016 (Griffin, 2023, para. 19; c.JASGP, n.d., para. 7), who currently manages Shōfūsō. The first major renovation under new management came in 1999 with a $1.2 million replacement of the hinoki bark roof, carefully replacing each tile (JASGP, 1999, p. 8.1; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 265; b.JASGP, n.d., para. 6). This was a “meticulous process… done completely by hand,” and it was restored again in 2011 and 2017, with the latest intervention costing $75,000 (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 265; Carroll, 2017, para. 1). According to Kim Andrews, current Director of JASGP, $100,000 is raised every five years solely for roof maintenance (RBF, 2020, 00:04:36). Although the cost is exuberant, and other Japanese teahouses in the United States have replaced their hinoki roofs with copper to reduce cost (JASGP, 1999, p. 8.2), it certainly seems worth it to maintain its status as the “only one of its kind outside of Japan” (b.JASGP, n.d., para. 6). (However, it may be appropriate to find cost-saving solutions. One forum poster suggests rubbing a hinoki cutting board with walnut oil to “seal” the wood [Aporigine, 2023]. Perhaps creative solutions such as this could be of some use, although I’ll leave that to the Japanese carpentry experts.)

-

The careful 2017 renovation of the hinoki bark roof at Shōfūsō (Carroll, 2017)

-

The careful 2017 renovation of the hinoki bark roof at Shōfūsō (Carroll, 2017)

Additionally, Shōfūsō saw another extensive renovation in 2007, including the donation by Hiroshi Senju of twenty nihon-ga (a type of traditional Japanese painting) murals. According to the JASGP (a.; n.d.), upon visiting Shōfūsō in 2004, Senju reflected that “I can sense the presence of Japan” (para. 3; Lee, 2009, para. 4). He was “inspired by [Shōfūsō’s] waterfalls,” replacing the Kaii Higashiyama black ink paintings previously damaged in vandal attacks in the 1970s, and “recreating Shōfūsō as a total work of art” (Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 265; Milroy, 2016, para. 2; Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 17; 19; a.JASGP, n.d., para. 1; c.JASGP, n.d., para. 7). His diligent work not only beautified the space, he helped to reaffirm the artistic integrity with which Yoshimura created Shōfūsō.

-

An example of Kaii Higashiyama’s black ink landscape (Huang-shan Mountains after the Rain, 1992). Similar paintings were originally installed within Shōfūsō (Higashiyama, 1992)

-

Hiroshi Senju’s nihon-ga painting Falling Water, 2013. Similar artwork replaced the damaged Higashiyama paintings at Shōfūsō in 2007 (Senju, 2013)

Similarly, the garden recently concluded its “massive” and “historic” renovation in Spring 2020 (a.JASGP, 2020, 00:01:31; Polyakov, 2021, p. 8). The original plans by Tansai Sano and David Engel, during Shōfūsō’s installation in Philadelphia in 1957, were never completed. Under the current head gardener, Sandi Polyakov, an intensive restoration went underway, capped off by the addition of a suhama pebble beach (Polyakov, 2021, p. 11). According to Gorichanaz (2016), Sano drafted “at least three distinct” garden designs (p. 6), and Polyakov’s team implemented the rocky shore from one of those archived plans. Polyakov noted in his report on the garden’s reconstruction (2021) that the implementation and development of the garden “evolved pragmatically with changes of administration and ephemeral influxes of funds and attention” throughout Shōfūsō’s history (p. 11), never fully being representative of Sano’s or Engel’s designs. This, however, is not unusual for Japanese gardens. According to Dr. Tomoki Kato, a leading landscape historian who works closely with the team at Shōfūsō, “Japanese gardens are ‘fostered’ through a ‘relay’ of lives… The garden is well-loved by various groups of people” throughout its lifespan. “I hope that it continues to receive such love” (Hironaka, 2020, 00:32:43). Under Polyakov and the rest of the team at JASGP, the garden certainly gets the attention it needs. As of 2013, Shōfūsō’s garden ranks as the third-best Japanese garden in North America by the Journal of Japanese Gardening (Pylant, 2015, para. 4; Gorichanaz, 2016, p. 4).

-

View of the garden in Philadelphia (Williams, 2022)

-

View of the carefully placed rocks in the pond (Pylant, 2015)

Today, the JASGP at Shōfūsō continues to fulfill its important cultural role. It boasts annual events such as Kodomo no Hi (Children’s Day) in May, Tanabata (Star Festival) in July, Obon (Buddhist Harvest Festival) in August, Otsukimi (Moon viewing) in September, as well as tea ceremonies hosted by the LaSalle University Urasenke Tea Program, demonstrations of origami, Ikebana (flower arrangement), and raku-yaki (pottery), plus Japanese language and taiko (drum) classes (JASGP, 1999, p. 7; Griffin, 2023, para. 7). A full calendar and class offering is available on the Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia website. These courses are hosted in their recently renovated Sakura Pavilion after the FJHG partnered with the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Department in 2012, costing a total of $684,300 (Rearick, 2012, para. 28-9; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 256-6). The 2020 CoVid-19 pandemic caused many programs to move online, but, in late 2020 after public spaces had reopened, visitation was “pretty much on par” with previous years (including my first visit), as “people… really value Shōfūsō and this is a place that they really want to come” (b.JASGP, 2020, 00:01:06). A full schedule of their class offerings is available on the JASGP website.

Unfortunately, on the other hand, the coronavirus pandemic recatalyzed anti-Asian sentiments in the United States. While there may have been reason to question the official story provided by the Chinese government, this uncertainty and distrust grew into attacks on Asians and Asian Americans with Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, or any Asian heritage (Ruiz, Im, & Tian, 2023, para. 3-5). In 2022, two years into the pandemic and after nearly all social-distancing precautions had been lifted, Shōfūsō suffered $2 million in damages from vandalism, including to Senju’s waterfall paintings. While there is “no evidence” that the attack was hate- or race-related (Mikati, 2022, para. 1-3; CCAHA, 2023, para. 1-2), it was the tragic culmination of two years of anti-Asian violence. To cap it off, the police response was less than admirable, as it took them seven hours to arrive on scene, believing Shōfūsō to be an Asian restaurant (Mikati, 2022, para. 20). Thankfully, astute workers at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts were able to mend the paintings “in such a way that the damage becomes unnoticeable” (CCAHA’s, 2023, para. 8), and Shōfūsō is back open for visitors. While anti-Asian sentiments seem to have dissipated within the endless culture war manifested by raucous politics, this flame has never truly died within the United States. It takes diligence and the open-mindedness to other cultures that Shōfūsō exemplifies to extinguish any lingering or resurgent hatred.

-

Senior Paper Conservator Heather Hendry at CCAHA works to repair Hiroshi Senju’s mural in 2022 (CCAHA’s, 2023)

Shōfūsō’s Importance to Architecture

Noticeably missing from the preceding pages has been a full detailing of the architectural features of Shōfūsō. A whole separate thesis could be written simply analyzing the intricate joinery or “the preservation of the natural curves of the tree trunk” within its beam work and its adoption by Vienna Secessionists (Peterson et al., 1955, 00:10:04; Drexler, 1955, p. 242). Yoshimura was very keen on the “purity of architecture,” describing it as “building materials used honestly, and structures composed only of the elements necessary” (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 8). Thus, this seventeenth-century shoin-zukuri house has profound implications to architecture in the West. Through the lens of Western architectural history, much of the description of detailing is largely unnecessary. Rather, like MoMA previously recognized for its House in the Garden exhibit, Shōfūsō is uniquely relevant to Modern architecture and design for its commitments to traditional Japanese building tenets.

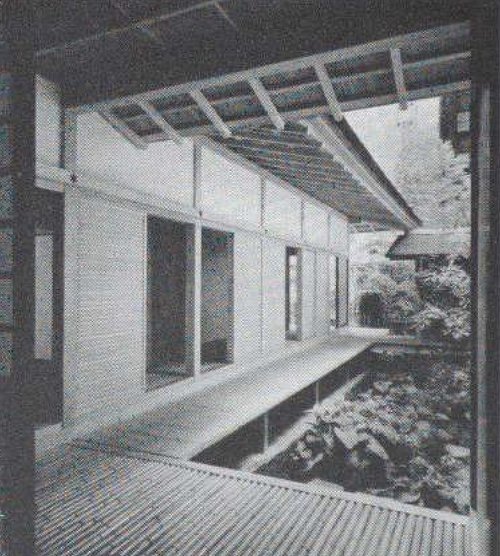

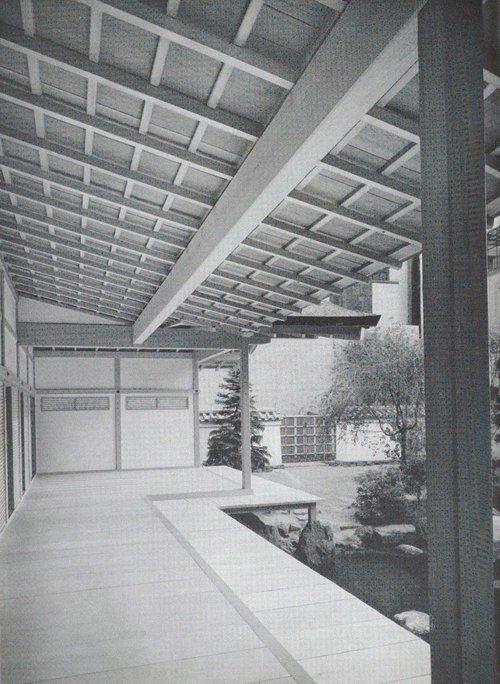

These tenets are: “post and lintel skeleton frame, flexibility of plan, close relation of indoor and outdoor areas, and the decorative use of structural elements” (MoMA, 1954, para. 2; Drexler, 1955, p. 262; RBF, 2020, 00:36:22). (However, as described henceforth, though they all intertwine in various ways, the two former and two latter tenets work with one another symbiotically, and shall be grouped as such.) Then it is obvious, according to Drexler, that “modern Western architects have borrowed so many ideas from the traditional architecture of Japan” that the Shōfűsō exhibition showed “the American the origin, in its purest form, of all those ideas and techniques we have so long admired” (Whitaker, 2022, p. 34). In response, Yoshimura himself argued that “traditional Japanese architecture was in and of itself modern” (Mikati, 2022, para. 8).

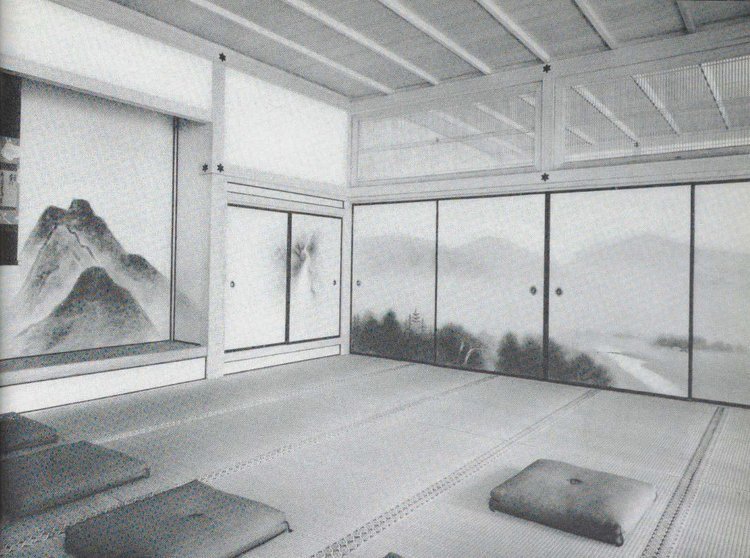

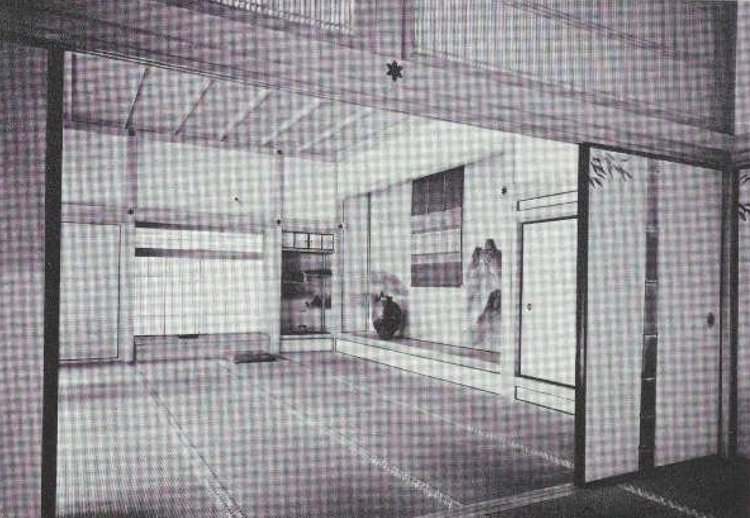

Photos from Exhibition #559 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (Drexler, 1955)

While Yoshimura created this house in the 1950s, the tenets from which he designed had been paramount to Japanese architecture throughout the Edo period in Japan (1603-1868). The similarities to Modern architecture of the mid-twentieth century are striking, and three-hundred years ahead of its Western counterpart. The first addressed is the Japanese insistence on flexibility, or as we may say today, minimalism. According to Peterson and the team at MoMA (1955), traditional Japanese architecture emphasizes “a profound absence of clutter” rather highlighting “space, light, air, openness of plan, and lightness of appearance” afforded by the skeletal structure (00:08:23). In crowded Japan, there is “practicality” in being able to put everything away and using a space for multiple purposes (JASGP, 1999, p. 9.4). Yoshimura achieved this at Shōfūsō with moveable fusuma panels to create “an ultimate flexibility of space” as well as built-in shelving and storage to highlight the home’s “clean lines and simple elegance” (JASGP, 1999, p. 10.3; RBF, 2020, 00:48:22). In a 1954 Newsweek editorial promoting the premiere of Shōfūsō at MoMA, the Japanese house was described as being “as free from extraneous objects as a Piet Mondrian painting” (Tadashi Oshima, 2022, p. 15). This was characteristic for much of Yoshimura’s work, as he believed that “design should be simple and clear… dedicated for people’s living and [their] spiritual richness” (RBF, 2020, 00:34:28).

This is directly influenced by his robust knowledge of traditional Japanese architecture and his decade-long experience under the visage of Antonin Raymond. Not unexpectedly, work from the modern masters such as Frank Lloyd Wright with his “massive, hovering, insistently horizontal” planes and the “open interiors and plain surfaces” of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe trace back to these traditional Japanese teachings (MoMA, 1954, para. 3; JASGP, 1999, p. 10.2; Chance & Toda, 2015, p. 97). According to Gattamorta & Perkins (2020), it is the Japanese “hierarchy of composition that generated harmonious geometric systems… [and] the simplicity and purity of materials” that were fundamental to successful architecture, becoming what today would be described as minimalism (para. 6). Further, now the organizational wizard Marie Kondo has become popular in the West for her commitment to these minimalist KonMari ideals (KonMari, n.d.). Like Modern architects and designers who learned lessons from uncluttered Japanese houses, contemporary homeowners continue to integrate these teachings into their lives.

Similarly, the Japanese insistence of the expression of nature was adopted by Modern architects and continues to be prevalent to this day. As had been seen in Philadelphia since the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, the Japanese refuse to delineate the “barriers between nature outside and the man-made interior” (Bareis, 2016, para. 1). Likewise, Yoshimura’s “profound connection with nature, experienced as an organic background, which… expresses the perfect unity between spirit and the material world” can be felt within Shōfūsō (Gattamorta & Perkins, 2020, para. 6). At Shōfūsō, take for example the engawa (veranda). From inside the house there is an immaculate view outside with “floor [to] ceiling windows,” framing the garden and koi pond as if a painting (RBF, 2020, 00:50:55; Hironaka, 2020, 00:25:38). Following the tenets of traditional Japanese architecture, Yoshimura avoided load-bearing or even any solid walls, creating an intimate yet “strong connection between the interior and exterior,” instead blurring the “relationship between man and nature” (JASGP,

Conclusion

Upon visiting Shōfūsō, most simply see a traditional Japanese house, and may feel enamored by its exotic expression of foreign architecture, exactly as Philadelphians had when faced with the buildings at the 1876 Centennial. Stepping inside, however, its wide berth of space and serene minimalism does not seem so unexpected: rather, it feels quite familiar (JASGP, 1999, p. 10.3). Its importance to Modern and contemporary architecture, while perhaps hidden within the traditional shoji and cypress pitched roof, still imposes itself on designers today. Even in 1955, Arthur Drexler noted that “just about every important architect had come to study” at Shōfūsō (JASGP, 1999, p. 10.2). The house perfectly blurs the line between traditional and contemporary, embodying the ideals of its creator: “We have to create contemporary architecture more and more,” Junzō Yoshimura says. “[We] cannot stay in nostalgia. Human beings always appreciate new inspiration and new development” (RBF, 2020, 00:32:05).

At Shōfūsō, the history gets obscured by its architectural beauty, its significance remains undiminished. “There’s a lot more to it” than its exterior, William Whitaker eloquently summarizes. It contains “the stories of the people who made it, the historical times on which it was created. It encompasses the vicious times of war, and the inhumane experiences of Japanese-Americans in this country” (Seymour, 2022, para. 9). Its unique history is intertwined with global conflict, racism and xenophobia, and horrible incompetence, but it is also replete with perseverance, commitment, and idealism. The Friends group in the 1980s and the Japan America Society which cares for it today have turned the house into a home. While no one lives there, it has been adopted by those who have felt marginalized, building and nurturing a community built on understanding, acceptance, and mutual respect. “A good house is one with something of a vague focal space,” Yoshimura ideates, “or a center of spatial gravity” (Ohi, 2022, para. 1). For Shōfūsō, perhaps the true center is and will continue to be those who care for it, and those for whom it cares. We are immensely fortunate to inherit this “special legacy” (JASGP, 2021, 00:23:35) that spans to the Centennial, the rich history of the Japanese in Philadelphia, the remembrance of mistakes made and opportunities for atonement, as well as the stress and love that went into its creation from Modern masters. While its history may have been turbulent, its future looks extraordinarily bright.

In the understated elegance of Shōfūsō, one discovers not just a glimpse of Japan’s architectural heritage, but a profound narrative woven intricately into the fabric of time. Beyond its picturesque exterior lies a legacy shaped by the convergence of tradition and innovation, where the echoes of past struggles and triumphs resonate within its walls. As Junzō Yoshimura envisioned, it stands as a testament to the perpetual evolution of architecture, transcending any particular time frame or style, rather embracing the boundless realm of new inspiration. The story of those who sought it out for its resilience and solidarity bridges cultures and generations with a welcoming sense of belonging. It transcends its materials, and even the material world; instead, it has emerged as a symbol of a future shaped by empathy, mutual respect, solace, and understanding. As its inheritors, we are tasked with preserving its enduring spirit, honoring the past while forging ahead towards a boundless tomorrow.

-

Junzō Yoshimura, ca. 1980s (Monma, ca. 1980s)

Bibliography

Aporigine. (2023, October 2). I have two hinoki boards, not Shun. First thing I did was apply walnut oil [Comment on the online forum post]. The care of a hinoki wood cutting board. ChefKnivesToGo Forum. https://www.chefknivestogoforums.com/viewtopic.php?t=17631

Bareis, K. (2016). Beginnings of Japanese influence on American design: The International Expo of 1876. Kezurou-Kai USA. https://kezuroukai.us/beginnings-of-japanese-influence-on-american-design-the-international-expo-of-1876/

Barr, J. (2018, November 3). Do | Co | Mo | Mo | Japan | 03: International house of Japan: Kunio Maekawa, Junzō Sakakura, Junzō Yoshimura. John Barr Architect. https://www.johnbarrarchitect.com/post/2018/11/01/docomomojapan03-the-international-house-of-japan-kunio-maekawa-junzo-sakakura-junzo-yoshi

Buscher, R. (2023, May 23). Recognizing Japanese American activism in the Watanabe collection. Philadelphia Museum of Art Blog. https://blog.philamuseum.org/recognizing-japanese-american-activism-in-the-watanabe-collection/

Carroll, T. (2017, October 11). 15 photos: Rare roof restoration uses material from Japan’s Imperial forest. Philly Voice. https://www.phillyvoice.com/15-photos-rare-roof-restoration-uses-material-from-japans-imperial-forest/

CCAHA’s expertise helps client recover from act of vandalism. (2023, March 6). Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts. https://ccaha.org/news/ccahas-expertise-helps-client-recover-act-vandalism

Chance, L. H. & Toda, T. (Eds.). (2015). Phila-Nipponica: An historic guide to Philadelphia & Japan (2nd Ed.). Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia.

Drexler, A. (1955). The architecture of Japan. Simon and Schuster. https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2711_300190118.pdf?_ga=2.223228187.1630918553.1710198991-1518462212.1710198990

Finkel, K. (2015, October 7). A story of stewardship. The Philly History Blog. https://blog.phillyhistory.org/index.php/2015/10/a-story-of-stewardship/

Gattamorta, G. & Perkins, S. (2020). Junzō Yoshimura (E. Frattini Magnusson, Trans.). Silent Masters. https://silentmasters.net/article/junzo-yoshimura/

Gorichanaz, T. (2016). A gardener’s experience of document work at a historic landscape site. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science & Technology, 53(1), 1-10. doi: 10.1002/pra2.2016.14505301067

Griffin, L. (2023, November 17). Cultivating a Japanese oasis in Fairmount Park. Hidden City. https://hiddencityphila.org/2023/11/cultivating-a-japanese-oasis-in-fairmount-park/

Hironaka, N. [Director]. (2020, October 20). A house in the garden: Shofuso and modernism [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ba2drsok3EM

Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. (1999). Historical Narrative of Shofuso. Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. https://japanphilly.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Historical-Narrative.pdf

a.Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. (2020, November 18). Interview with James Webster [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eb9AXPeArKc

Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. (2021, July 2). Shofuso and modernism curators talk [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4G9471aywg4

Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. (2023). Okaeri (Welcome Home): The Nisei Legacy at Shofuso. Philadelphia, PA. https://okaeri.japanphilly.org/intro

a.Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia (n.d.). Hiroshi Senju paintings. Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. https://japanphilly.org/shofuso/shofuso-history/hiroshi-senju-paintings/

b.Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. (n.d.). Organizational history. Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. https://japanphilly.org/about/who-we-are/organizational-history/

c.Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. (n.d.). Shofuso history. Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. https://japanphilly.org/shofuso/shofuso-history/

KonMari philosophy: What is Kurashi? (n.d.). KonMari.com. https://konmari.com/what-is-kurashi/?utm_source=top%20right%20tile%20&utm_medium=Kurashi&utm_campaign=homepage

Lee, C. M. (2009, Fall). An Asian ambassador to Philadelphia. Penn State University Libraries: Pennsylvania Center for the Book. https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/feature-articles/asian-ambassador-philadelphia

Lindsey, R. (1982, April 6). Resentment of Japanese is growing, poll shows. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1982/04/06/us/resentment-of-japanese-is-growing-poll-shows.html

Mikati, M. (2022, September 2). ‘It’s happening again’: Shofuso vandalism awakened generational trauma, community support. Philadelphia Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-shofuso-rebuilds-after-vandalism-20220902.html

Milroy, E. (2016). Fairmount park. The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/fairmount-park/

Museum of Modern Art. (1954). Japanese exhibition house, the Museum of Modern Art, summer, 1954. Designed by Junzō Yoshimura. Sponsored by the America-Japan society (Tokyo) and private citizens in Japan and the United States, and the Museum of Modern Art [Press release]. https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2711_300380245.pdf?_ga=2.223228187.1630918553.1710198991-1518462212.1710198990

Nio-Mon, or temple gate. (1906, January). Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum, 13(4), 12. doi: 10.2307/3793774

Ohi, T. (2022, March 30). Junzo Yoshimura, Sonoda house: Sliding glass door leading to the garden and waist-high window making a space somewhat core to the design. Window Research Institute. https://madoken.jp/en/series/12615/

Oi, M. (2015, August 9). The man who saved Kyoto from the atomic bomb. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-33755182

Peterson, S. [Producer], Museum of Modern Art, and Shofuso Japanese House and Garden. (1955). A Japanese house: An impression of the Japanese exhibition house in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art, 1953-1955 (Shofuso at the Museum of Modern Art 1954-1955) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cq1YbjWzD78

Philadelphia: America’s Garden Capital. (n.d.). Philadelphia’s Japanese and Asian gardens. The AGC Blog. https://americasgardencapital.org/philadelphias-japanese-and-asian-gardens/

a.Philadelphia Museum of Art. (ongoing). Collecting Japanese art in Philadelphia. Philadelphia, PA. https://philamuseum.org/calendar/exhibition/collecting-japanese-art

b.Philadelphia Museum of Art. (ongoing). Collection highlight: Ceremonial teahouse. Philadelphia, PA. https://philamuseum.org/calendar/exhibition/collection-highlight-ceremonial-teahouse

Polyakov, S. (2021). Shofuso’s suhama pebble beach project. Journal of the North American Japanese Garden Association, 8, 8-16.

Pylant, D. (2015, June 5). Shofuso Japanese house and garden 松風荘. North American Japanese Garden Association. https://najga.org/reference/shofuso/

Rearick, K. (2012, April 13). Sakura pavilion open at Japanese house and garden in Philadelphia. NJ.com. https://www.nj.com/gloucester-county/towns/2012/04/sakura_pavilion_open_at_japane.html

Rockefeller Brothers Fund. (2020, November 24). Pocantico virtual fall forum: Modern Japanese architecture and design in America [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hw8am66-84A

Ruiz, N. G., Im, C., & Tian, Z. (2023, November 30). 4. Asian Americans and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-ethnicity/2023/11/30/asian-americans-and-discrimination-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

Scott, C. (2020, September 27). Ugly story from American history, inspiring stories of art, on view at Shofuso Japanese house and garden. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/chaddscott/2020/09/27/ugly-story-from-american-history-inspiring-stories-of-art-on-view-at-shofuso-japanese-house-and-garden/?sh=37ba87774d27

Seymour, T. (2022, July 7). Japanese architecture, craft and Modernism meet in Philadelphia. Wallpaper. https://www.wallpaper.com/architecture/japanese-house-shofuso-and-modernism-exihbition-philadelphia-usa

Tadashi Oshima, K. (2022). Found in translation. In Whitaker, W. & Yokoyama, Y. (Eds.), Uncrating the Japanese House: Junzō Yoshimura, Antonin and Noémi Raymond, and George Nakashima (pp. 11-25). August Editions.

Tanaka, H. (2011, February 22). US-Japan relations: Past, present, and future. In New Shimoda Conference: Revitalizing Japan-US Strategic Partnerships for a Changing World: Conference Report (pp. 50-56). Japan Center for International Exchange.

Time Magazine. (1965, July 9). Architecture: The emperor’s new palace. Time Magazine Archive. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,833939-1,00.html

Ujifusa, S. (2010, May 12). Japan-a-mania at the Centennial. The Philly History Blog. https://blog.phillyhistory.org/index.php/2010/05/japan-a-mania-at-the-centennial/

Watanabe, M. (1985). Early Philadelphia Issei. The Japanese American Experience: An Exhibition in the Museum of the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies. https://www2.hsp.org/exhibits/Balch%20exhibits/japanese/earlyphila.html

Wellerstein, A. (2020). The Kyoto misconception: What Truman knew, and didn’t know, about Hiroshima. In Gordon, M. D. & Ikenberry, G. J. (Eds.), The Age of Hiroshima (pp. 34-55). Princeton University Press.

Whitaker, W. (2022). Arthur Drexler, Yoshimura Junzō, and the inside story of exhibition #559. In Whitaker, W. & Yokoyama, Y. (Eds.), Uncrating the Japanese House: Junzō Yoshimura, Antonin and Noémi Raymond, and George Nakashima (pp. 27-51). August Editions.

Whitaker, W. & Yokoyama, Y. (Eds.), (2022). Uncrating the Japanese House: Junzō Yoshimura, Antonin and Noémi Raymond, and George Nakashima. August Editions.

Further Research and Exhibits

Admin. (n.d.). Shofuso Japanese house and garden [Forum post]. Philadelphia Archaeological Forum. https://www.phillyarchaeology.net/philly-archaeology/archaeological-sites-of-interest/sofuso-japanese-house-and-garden/

Do Co Mo Mo. (2016, October). Modernism and Japanese carpentry: Preserving the architecture of Junzō Yoshimura. Bucks County, PA. https://www.docomomo-us.org/event/modernism-and-japanese-carpentry-preserving-the-architecture-of-junzo-yoshimura

Doebler, P. L. (2017). Imaginative intersections: Engaging aesthetic experience at the Shofuso Japanese house. Contemporary Aesthetics, 15(19), 1-10. https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/liberalarts_contempaesthetics/vol15/iss1/19

Flock Finger Lakes. (2022, April 19). Quintessential Japanese garden & architecture tour: Shofuso – Ep. 088 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TJriJlkTPbg

b.Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia. (2020). Shofuso and Modernism. Philadelphia, PA. https://www.shofusoandmodernism.com

Japanese tea ceremony in the Philadelphia region. (n.d.). Urasenke Philadelphia. https://phillytea.org/

Kruger, N. (2013, November 1). Bearing witness: Junzō Yoshimura and the Sanrizuka church. Artscape Japan. https://artscape.jp/artscape/eng/focus/1401_02.html

North American Japanese Garden Association. (2016, September 22). Junzō Yoshimura: A Japanese garden experience in Manitoga. North American Japanese Garden Association. https://northamericanjapanesegardenassociation.wordpress.com/tag/junzo-yoshimura/

Philadelphia Museum of Art. (1988-1989). The arts of tea. Philadelphia, PA. https://philamuseum.org/calendar/exhibition/the-arts-of-tea

Rowe, J. M. (2011, June 13). Eitokusai’s dolls in Japan. Temple University Anthropology Lab Blog. https://anthropologylabtemple.wordpress.com/2011/06/13/eitokusais-dolls-in-japan/

Susoki, P. (2014). The new visitor center at Shofuso: Expanding site interpretation through new construction [Graduate thesis, University of Pennsylvania]. UPenn Repository. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/553

Yale University School of Architecture. (2019). Japan, archipelago of the house. New Haven, CT. https://www.architecture.yale.edu/exhibitions/57-japan-archipelago-of-the-house

Images not from prior sources

Centennial Exhibition 1876 Philadelphia Scrapbook [Photograph]. (1876). Free Library of Philadelphia. https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/2402

Centennial Photographic Co. (1876). Japanese Bazaar [Photograph]. United States Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3c25801/

Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. (2024). 1917-1923 - Wright designs the Imperial Hotel, Tokyo. 1905: Japan Through the Lens of Frank Lloyd Wright. https://www.wrightsjapan1905.org/timeline/the-imperial-hotel/

Higashiyama, K. (1992). Huang-Shan Mountains after Rain [Lithograph]. Japanese Painting Gallery. https://www.japanese-painting.com/artist/kaii_higashiyama/artwork/2013-huang-shan_mountains_after_rain.html

Japanese Garden and Pagoda, Fairmount Park [Photolithograph]. (ca. 1930). Free Library of Philadelphia. https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/63756

Kramer, B. (1954). “Private showing before opening” [Photograph]. Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711?installation_image_index=55

Kramer, B. (1955). Shin-ichi-Yuzie [Photograph}. Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711?installation_image_index=70

Kojoin Garden [Photograph]. (2019). Miidera Museum of Cultural Heritage. https://miidera-museum.jp/en/cultural-property/contents/21/

Kojoin Reception Hall [Photograph]. (2019). Miidera Museum of Cultural Heritage. https://miidera-museum.jp/en/cultural-property/contents/21/

MoMA. (1956). Installation view of the exhibition “Japanese Exhibition House” [Photograph]. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711?installation_image_index=1

Monma, K. (ca. 1980s). Yoshimura Junzō [Photograph]. Window Research Institute. https://madoken.jp/en/series/12615/

Museum of Modern Art. (1954-1955). Japanese exhibition house. New York, NY. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711

Senju, H. (2013). Falling Water [Painting]. Sundaram Tagore Gallery via Meer Art. https://www.meer.com/en/2656-hiroshi-senju-day-falls-slash-night-falls

Shofuso. (2018, January 23). We’re 60 days away from Shofuso’s reopening! That’s one day for each year that Shofuso has been in West Fairmount Park, seen here in 1958 [Image attached] [Status update]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/Shofuso/photos/a.411332899178.201807.304088964178/10156875012274179/?type=3&theater&_rdr

Shofuso Japanese House and Garden. (2017, October 10). Raising the roof by Keiichi Kondoh: Shofuso’s 1999 roof restoration [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=76xKEWmF2mA

Stoller, E. (1954). Installation view of the exhibition [Photograph]. Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711?installation_image_index=3

Sunami, S. (1954). Meal after ridge beam ceremony [Photograph]. Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711?installation_image_index=51

Sunami, S. (1954). “Visitors at opening” [Photograph]. Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711?installation_image_index=58

Sunami, S. (1955). Installation view of the exhibition [Photograph]. Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711?installation_image_index=1

Sunami, S. (1956). Japanese House in the Museum garden [Photograph]. Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2711?installation_image_index=79

Temple drum (Moku-Gyo) [Photograph]. (n.d.). Philadelphia Museum of Art. https://www.philamuseum.org/collection/object/136614

Wescott, T. and Hunter, T. (1876). Japanese Bazaar [Photograph]. Free Library of Philadelphia. https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/2174

Widman, G. (2008). Shofuso waterfall [Photograph]. Penn State University Libraries: Pennsylvania Center for the Book. https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/feature-articles/asian-ambassador-philadelphia

Williams, T. (2022). Shofuso garden and pond [Photograph]. Philadelphia Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-shofuso-rebuilds-after-vandalism-20220902.html

Williams, T. (2022). Shofuso house and garden [Photograph]. Philadelphia Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-shofuso-rebuilds-after-vandalism-20220902.html