Case Study: Paoli, PA

How Transportation Built a Town

Paoli Station, now (2017)

Originally submitted as part of the curriculum at Temple University | April 19, 2018

Transportation has always pushed civilization to expand. Feet carried mankind to the shores, boats washed them across channels, seas, and oceans, trains traced through the ever-changing landscape, and cars cemented expansive local accessibility. The slow technological march of transportation advancement replaced each mode indiscriminately. As new types of transit became more accessible and popular, people moved further from their work in the city. Across the nation (as the United States drove automobile- and transit-oriented suburbanization), city workers moved into the suburbs.

Philadelphia saw no exception. Along the turnpikes established as Pennsylvania incorporated, and along the railroads cast adjacent, neighborhoods, communities, and towns developed. But Paoli is unique: it’s a small “census-designated place” – not even a town – embedded in massive regional townships. Throughout the entire push into the Delaware Valley hinterland, residents from neighboring Tredyffrin, Easttown, Willistown, and Malvern townships commuted – and continue to commute – to Philadelphia from Paoli Station. But the intense focus on automobile transit and accessible roadways has brought about some incredible changes and staggering problems. Paoli now has the opportunity to improve its own accessibility and municipal sustainability and transform its commuter-oriented community.

Transit, as it had with similar towns in essentially every part of the nation, built Paoli. Even before coal, steam, gas, or electric powered automatic modality, Paoli was a popular destination. In the days of the horse-drawn buggy, Paoli, about twenty miles east-northeast of Philadelphia, was one full day’s travel into the country. In 1769, a savvy entrepreneur named Joshua Evans established the Paoli Inn – the original epicenter of the village – named for Pasquale Paoli, a Corsican general who vanquished the Genoese Italians just twenty years before (“Paoli, Pennsylvania,” n.d.).

Situated a full day away, inn-keeping was a wise occupation, and even the very inception of this village relied upon manual transportation accessibility. Around this inn, along the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, the community slowly grew. According to an 1875 pamphlet entitled “Suburban Stations and Rural Homes on the Pennsylvania Railroad,” “Paoli was a noted point on the Lancaster Turnpike before railroads were constructed” (Goshorn, 1981). More than a century after it opened, the Paoli Inn burned down in 1899 and was replaced by two other inns, “both of which originally served as hostelries for the Lancaster Turnpike” (Nassau III, 2003). The town’s initial growth is indebted to westward expansion, but eventually benefitted from all types of transportation.

-

Paoli in 1875, as shown in Suburban Stations and Rural Homes on the Pennsylvania Railroad

The village before suburbanization more-or-less epitomized the “picturesque enclave.” In “Suburban Stations,” it was described as “an old settlement, in the midst of some beautiful scenery. Pleasant groves are here, and shady roads lead into the adjacent country, passing through valleys and over gentle hills, where many scenes of beauty and interest can be discovered” (Goshorn, 1981). Southeastern Pennsylvania, west of Philadelphia, was lush with gorgeous natural scenery and became a popular summer recluse from the heat of the city. By 1875, the pamphlet noted that “many beautiful homes are erected each year to supply the constant demand for them” (Goshorn, 1981).

By this time, however, as hinted by the title of the local publication, the Pennsylvania Railroad (which had replaced the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad) was already in full service. With a six-cent ticket ($8.70 monthly), commuters could reach Philadelphia in just thirty-seven minutes on the express or fifty-three minutes local. “Under these conditions,” the pamphlet proposed, “the suburban resident may reach his rural home while his less fortunate city brother is still plodding homeward by the slower means of transportation which depends on horseflesh for its motive power” (Goshorn, 1981). Accessibility provided by frequent trains allowed for what was once an inn to develop into the village it has become.

The railroad – and the democratization thereof – was extremely beneficial to Philadelphia suburbs. With a new train station, Paoli, although already established, became markedly more attractive to the suburban settler. At the height of Pennsylvania Railroad’s tenure, the company developed a plan for high-density housing within a one-mile radius around Paoli’s train station. It fizzled out before the project was completed, but not before the Tredyffrin-Easttown population doubled, jumping from 2,820 people to 4,210 (Goshorn, 1981).

By 1913, forty-five express and local trains served the upper Main Line on weekdays, as well as twenty-eight additional trains on Sundays. The rail pamphlet published that year, renamed “Thirty Miles Around Philadelphia on the Lines of the Pennsylvania Railroad,” noted that the “low rates of fares maintained, the high-class service and the various forms of tickets provided (are) features which must prove attractive to the suburban dweller, as well as materially aid in the future development of this entire region” (Goshorn, 1981). Before automobiles became readily accessible, the commuter railroad effectively suburbanized the Delaware Valley.

-

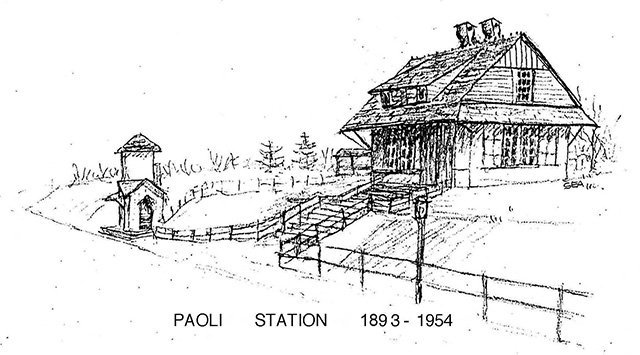

Paoli Station, 1893-1954

Around the turn of the century, cars were becoming increasingly popular. The electrification of the rail came too late to save the village from paving their roads and turnpike. With personal automobiles and winding, endless roads, the popularity of the train dipped. By the mid-twentieth Century, poor service and decrepit, deteriorating equipment alienated commuters, and ridership dropped rapidly (Nassau III, 2003). However, this did not deter suburbanites from developing homes in the Paoli countryside. According to The Architectural Record, volume 36:

“The beginning of this new country house phase of American life was made possible by the development of the suburban service of the various railroad systems. The evolution and expansion of this service has brought tremendously wide areas within the suburban zone which sometimes has a radius extending fifty miles or more from the civic center. The work begun by the railroads has been perfected by the automobile and every portion of the country rendered readily accessible”

(Eberlein, 1914, p. 321).

The population of the region in which Paoli is situated exploded in the twentieth Century. Paoli and Malvern are urban-suburban (Paoli has a density of 2,787 and-a-half people per square mile), and the surrounding townships – Tredyffrin, Easttown, and Willistown – are all classically suburban. The automobile wrought wholesale changes to the design of the town. Roads and turnpikes had to be paved, and traffic laws had to be adapted. As early as 1901, Paoli residents were advocating for traffic signals, after the Main Line Limited reported that a driver had hit-and-run a wagon (“An early plea for traffic laws in Paoli,” 1901).

There was a bit of push-back against the auto industry. As the Lancaster Turnpike was paved and turned over to the Pennsylvania government, Paoli experienced a culture-shock that they worked hard to prevent. In 1911, a proprietor who owned a garage in neighboring Berwyn tried to open a second location in Paoli. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Paoli officials rejected his request, dissenting: “it would be offensive and a danger to the neighborhood” (“Club members remember: the changing face of Paoli,” 1989). Eventually, however, the automotive industry started to take hold. In 1921, Matthews’ Ford opened near the train station, the first Ford dealership in the region – which still operates today (“About,” n.d.; “Club members remember,” 1989). As well, the stable where commuters would ride to catch the train was upended by the auto (Nassau III, 2003), and concurrently replaced by a repair garage (“Club members remember” 1989). The car was here to stay.

-

Matthews’ Ford (now Paoli Ford), the first auto dealer in the area. Circa 1924 to 1930.

By 1960, Paoli was firmly developed. In the previous decade, the village saw a 144% population increase (Goshorn, 1981). This was when houses were ripe for the picking, popping up in every corner of the metropolitan – in the cradle of modern suburbia. With the closing of Broad Street Station – the commuter hub in Philadelphia – and the opening of Suburban Station, driving into the city became ever-more attractive. The region fully took to the automotive industry, and at mid-Century, there were thirteen service gas stations just in Paoli. One historian speculates that this was necessary because of poor gas mileage, and he may be right: as of 2003, there are now only three gas stations in town (Nassau III, 2003). Cars had already shaped the suburbs before they were any sort of definition of efficient.

Today, driving into Philadelphia is simply not fun. So, instead of sitting in traffic and struggling to find a parking space, commuters have switched back to riding the train. Paoli Station – the western terminus on the Paoli line on the Regional Rail – sees a massive influx of passengers every day. Although its population as of the 2010 Census is a mere 5,575 people, its 2013 ridership topped 900,000 people (Pirro, n.d.). That’s about 3,500 people each weekday, nearly all of whom come from the surrounding townships.

“[Paoli Station is] one of the busiest in the metropolitan and the state. It’s so bustling that the building and parking facilities can no longer accommodate the volume. Paoli merchants remain frustrated by commuters consuming the limited downtown spaces, while buses and shuttles squeeze into the cramped parking lots adjacent to the station”

(Pirro, n.d.).

This is a massive problem for the small town, especially the tiny business district. One resident noted, “you’re looking into a city, but it’s not breathing, so no one is motivated to come shop. It’s still a bedroom community with train access to Philadelphia, but not a business community” (Pirro, n.d.). When the Pennsylvania Railroad operated, they envisioned high-density housing nearby for people to walk to the station. Before that, people rode on horseback to the station. Today, interlocutor commuters ride their metallic beasts. Cars completely upended the commuter rail, and now we face the repercussions.

Thankfully, the operators see the need for improvements. The new Paoli Intermodal Transportation Center, a joint project by SEPTA, Amtrak, PennDOT, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, Chester County, and Tredyffrin Township, as well as several public and private stakeholders, is slated for completion in the early 2020s. This project consists of three phases, and will completely transform the standard, cookie-cutter platform. The first phase is to improve station accessibility to comply with the 2006 Americans with Disabilities Act. New ramps, elevators, and escalators are being installed to accommodate people who may require non-stair options. The second phase is renovating the highway intersection and erecting bridges for easier pedestrian access and better traffic flow. The third phase will see the construction of the new intermodal terminal and a parking garage, providing adequate space and giving relief to the desperate merchants (“Paoli on the move”). This innovative and scrupulous project will alleviate many of the problems that the town faces today.

-

A 3D rendering of the proposed Paoli Intermodal Transportation Center.

Additionally, high-density residential towers will be completed with the new station. Not only will this provide accessible housing near the station, it will reduce the need to drive to (and park at) the station. But there is an additional benefit: with the proximity of the available housing and the new parking garage, commuters will not take up all of the town parking. Lauren Wylonis, the CEO of KingsHaven Design – the firm tasked with designing the apartments, succinctly states their goal: “The Main Line has continued to extend westward over the last forty years, and we believe it’s time for Paoli to come into its own as a real destination town” (Pirro, n.d.). A successful business sector is essential to sustainability. Paoli never had any Pennsylvania industry, and it has struggled to make its market attractive. This comprehensive joint venture – the intermodal transportation center and the adjoining complexes – will provide the infrastructure backbone to ease of access necessary for a blossoming shopping district. Once again, residents will be able to stroll in town, and walk - scratch that: sprint - to their train.

This report probably isn’t a traditional case study. But in my research, transportation was a resounding theme – Paoli’s inception, development, rapid changes, and now immense problems revolve around the advancement – and limitations – of transportation technology. But this conscientious and comprehensive renovation of the entire transit lot will solve multiple problems in one fell swoop.

While organizing and developing a thesis, my findings were reminiscent of other cities that have addressed their transportation headaches: Curitiba, Phoenix, Seoul – and others that planned their cities around transportation routes, like Hiroshima and even Brasilia. They all face different issues, primarily congestion due to population explosions. But all of these cities have successfully implemented developments that promote better pedestrian, bike, automobile, and transit accessibility which in turn opens the entire city to just about everyone. This benefits all facets of sustainability, from pedestrian accessibility cutting down on the use of cars and conscientious design for ease of access, to opening up the downtown “Main Street” and promoting in-town involvement. In a town built from transportation, they are now innovating to solve the 21st Century dilemmas.

Although the plan addresses pedestrian accessibility in and around the train station, there is a need for accessibility and walkability within the whole town. It’s fairly tiny – only two square miles – perfectly walkable for anyone in-town. But Paoli is constantly flooded with commuters from the surrounding townships, vying for a space indiscriminately. The pattern of design without foresight has only proven to be burdens on modern commuters.

The capital of my home state was developed following colonial cow trails (and segregationist residential development). Like anywhere, the rush hour congestion in Boston is nightmarish; however, navigating the winding streets and incomprehensible one-ways is an utter sh*tshow to anyone but the seasoned commuter. I grew up thirty minutes outside of the city (almost everywhere in Massachusetts, as well as southern New Hampshire and northern Rhode Island/northeastern Connecticut, is under ninety minutes away), and I loathed driving into Boston. The commuter rail was my haven, despite the towns of Massachusetts being developed on rivers and canals, not railroads. But the problems of unplanned suburbanization – sprawl – are universal. Here in Philadelphia, I refuse to drive. I commute on the Market-Frankford “El” to the Broad Street Line to get to class, and I walk to work (it’s two minutes from my apartment). I’ll Uber if I’m intoxicated, but that’s not too often. But as I have witnessed, and as Paoli has recognized, mass transit and pedestrian accessibility is key to the modern sustainable city and suburban worker.

Paoli from its inception was a sleeper town. Its main attraction has historically been its access to Philadelphia – first on Lancaster Turnpike, and then on the Pennsylvania Railroad – and it continues to be a massive hub for Chester County commuters. But in redesigning their centerpiece, the town can become an attraction in itself. This development will not only revive the attractiveness of Paoli’s downtown, but it will also satisfy all facets of sustainability.

One final thought; ubiquitous redesign to improve walkability throughout its entire two square miles would reduce the need for cars and would be an opportunity to add green space. One author laments about the hindrance of the government red tape: “At the turn of the century prominent citizens would recognize a need and then get their friends together to provide a solution” (Nassau III, 2003).

But by now, the community is so completely developed leaving no room for anything but private or government development. And as we have witnessed, private development has disregarded any semblance of efficient design. But in Paoli and other cities, government projects have helped to clear congestion and improve accessibility. To implement sustainable practices, there needs to be a leading force in ensuring developments and designs are sustainable. This does not mean only LED lighting and energy-saving windows are required. Sustainability extends into our design for cars and pedestrians, our layout for commuter transit, and our in-town economy. With the new Paoli Intermodal Transportation Center, various public and private agencies – led by the Pennsylvania authorities – have recognized and addressed the sensible sustainability needs of the town. In one design, they will completely revolutionize the village. Imagine what we can do for the rest of Pennsylvania.

References

“About.” (n.d.) Retrieved from Paoli Ford website: https://www.paoliford.com/dealership/about.htm

“An early plea for traffic laws in Paoli.” (1901, August 15). Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v18/v18n3p082.html

“Club members remember: The changing face of Paoli.” (1989, July). Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v27/v27n3p102.html

Eberlein, Harold D. (1914, October). “Five phases of the American country house.” The Architectural Record Index-Volume XXXVI (pp. 273-341). New York City: The Architectural Record Co.

Goshorn, Bob. (1981, January). “When the Pennsylvania Railroad promoted suburban living.” Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v19/v19n1p013.html

Nassau III, William. (2003, April). “Paoli then and now: a social transition 1900 to 2000.” Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v40/v40n2p063.html

“Paoli on the move.” (n.d.). Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Township website: http://www.tredyffrin.org/projects/paoli-on-the-move

“Paoli, Pennsylvania.” (n.d.). Retrieved from City-Data website: http://www.city-data.com/city/Paoli-Pennsylvania.html

Pirro, J.F. (n.d.). “Can a new train station transform Paoli?” Retrieved from Main Line Today website: http://www.mainlinetoday.com/Main-Line-Today/January-2016/Can-a-New-Train-Station-Transform-Paoli/

Image Bibliography Annex

Baist, G. W. [cartographer] (1887). “Atlas of properties along the Pennsylvania R.R. from Overbrook to Malvern station, 1887” [image]. Retrieved from Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network website: https://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/view-image.cfm/JLS1887.OverbrookToMalvern.004.PhiladelphiaVicinity

“Chester County 1873” [image]. (n.d.). Retrieved from Historic Map Works website: http://www.historicmapworks.com/Atlas/US/7069/Chester+County+1873/

Further Research

Bennett, Max. (2018, January 9). “Gov. Wolf cuts ribbon at Paoli business Monday.” Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Patch website: https://patch.com/pennsylvania/te/gov-wolf-cuts-ribbon-paoli-business-monday

Gibson, Philip. (2007, Summer). “The importance of the Paoli Massacre.” Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v44/v44n3p093.html

Goshorn, Bob. (1985, October). “Remember Paoli! A portfolio of poems.” Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v23/v23n4p137.html

Goshorn, Bob. (1980, October). “When a presidential candidate campaigned in Paoli.” Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v18/v18n4p119.html

Goshorn, Robert, and Geasey, Robert. (1996, October). “The electrification of the Paoli local.” Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v34/v34n4p127.html

“Historic Paoli landmark saved: a pictorial report.” (1986, July). Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v24/v24n3p105.html

Landeck, Carl, and Thorne, Roger. (2005, Spring). “The Pennsylvania Railroad during World War II.” Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v42/v42n2p035.html

“Landscapes 3 comprehensive plan.” (2018). Retrieved from Chester County Planning Commission website: http://www.chescoplanning.org/CompPlan.cfm

“Paoli, PA.” (2013). Retrieved from Amtrak’s Great American Stations website: http://www.greatamericanstations.com/stations/paoli-pa-pao/

“Paoli, Pennsylvania.” (n.d.). Retrieved from Wikipedia.org website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paoli,_Pennsylvania

“Pasquale Paoli.” (n.d.). Retrieved from Encyclopedia Britannica website: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Pasquale-Paoli

Peterson, Charles J. (1843, November 1). “Paoli: A story of Pennsylvania.” Graham’s Magazine of Literature and Art, pp. 249-264.

Reedy, Ronald. (2002, August). “Columbia Rail History.” Retrieved from Columbia Historic Preservation Society website: https://columbiahistory.net/train/history/

“The Paoli inn.” (1965, April.) Retrieved from the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives website: http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v13/v13n3p056.html