Sustaining the Suburban Lawn

Flowers, Trees, and Bees

Feature photo from here

Originally submitted as part of the curriculum at Temple University | April 1, 2018

View the accompanying presentation here

Abstract

The continuous expanse of green short-cut grass is the most recognizable and ubiquitous feature of the American suburbs. In understanding how the nation has so uniformly implemented this type of landscape, we can discern the true uselessness and harmfulness of lawns. Instead, with consideration to the triple bottom line of sustainability – people, planet, and profit - we can find new solutions to achieving healthy and sustainable suburban home environments.

Lawns could be the official landscape of the United States – or of humans, for that matter. Humans are genetically inclined to trimmed lawns akin to the short Bermuda grass of the East African savannas upon which we evolved (Kolbert, 2008). This aptly named “Savanna Syndrome” (Pollan, 1989), although now nearly ubiquitous in the United States, and despite its ancient roots, is not how humans lived for ninety-five percent of our history. The first mowed lawns were purposeless aside from serving as a symbol of elite status (Kolbert, 2008; Baker, 2015), and emerged on eighteenth-century English manor estates, within French gardens, and as early as the sixteenth century in Italian painter Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (Garber, 2015; Brown 2011; Kolbert, 2008). Since estate-owning nobility did not have to rely on farming their own land for food, livestock could graze or servants could scythe, keeping their lawns short (Kolbert, 2008). In moving to the new world, colonists brought this ideal elite landscape. Since the only native North American grass is Buffalo Grass, covering the Great Plains from Montana to Mexico (Kolbert, 2008; Duble, n.d.), American colonies imported English grass seed (Brown, 2011) for livestock to graze. Although, lawns at this point were still reserved for those who did not have to rely upon farming their own land. Elite examples of early American lawns include George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate in Fairfax County, Virginia, and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate outside Charlottesville (Borelli, 2017), both of which established the “ambitions of a newly formed nation” (Garber, 2015).

-

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello Virginia estate, flaunting its vast lawns.

-

George Washington’s Mount Vernon Virginia estate, flaunting its vast lawns.

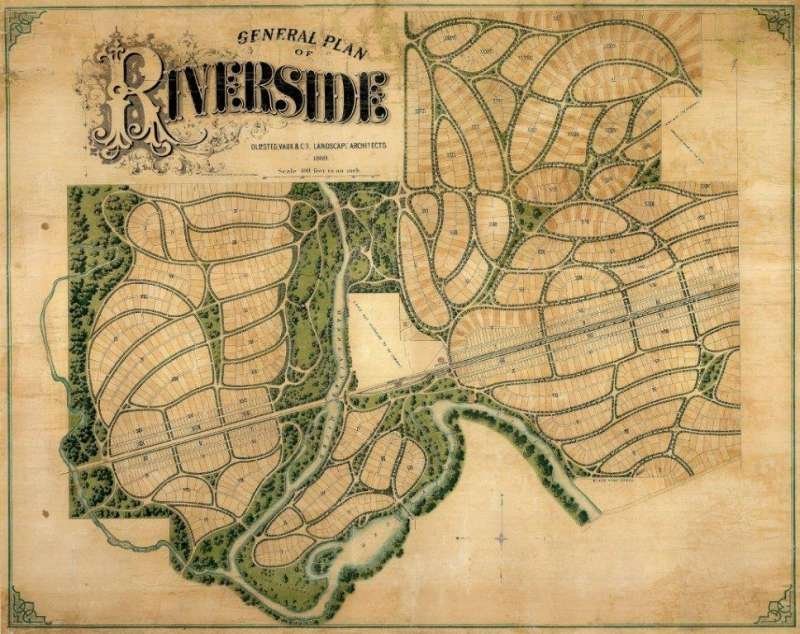

The vast expanse of green that the United States boasts now, however, is no longer solely reserved for the elite. The Industrial Revolution and technological advances helped to democratize the estate-style lawn. The first egalitarian American lawns started to emerge in the mid-nineteenth century, as the first “picturesque enclaves” and suburban straits were developed. In fact, architectural and landscape visionary Andrew Jackson Downing recommended that homes feature an expanse of “grass mown into a softness like velvet” (Kolbert, 2008). Though he also promoted cultivating herb gardens in a small plot in his 1841 Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (Hayden, 2003), the shaved lawn pervaded into American suburbs. Downing’s style influenced some of the first modern suburbs in the United States, particularly Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1869 development in Riverside, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. First in unifying suburban communities, with his short-cut lawns connecting each property to the next, wanted to create “the impression that all lived together in a single park” (Pollan, 1989). Olmsted established strict land-use covenants for house placement and lawn standards in his Riverside installation. These were necessary to maintaining order because, according to Hayden (2003), “public park areas along the river were defined by the design, [but] private lots covered most of the available land for building, and private investment in lots was key to the developers’ success” (p. 64). At this point, it was clear that mass-produced suburban plots and lawns were a landscaping gold mine. Though these practices served to establish suburban uniformity, it was the landscape of which Ernest Hemingway described as having “wide lawns and narrow minds” (Borelli, 2017).

-

The original plans for Olmsted’s Riverside development in Illinois.

Despite critical writers’ melancholy sentiments on the new American landscape, lawns persisted. Not one year after Olmsted completed Riverside, Frank J. Scott published his Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds, and, eager to democratize suburban amenities, described “a smooth, closely shaven surface of grass” as “essential” (Pollan, 1989). Along with the advent of machine lawnmowers (Kolbert, 2008), the turn of the twentieth century brought national organizations like the Garden Club of America promoting manicured and uniform lawns. As well, joint federal and commercial ventures pushed to expand the geographic range of soft, short grass. In the 1930s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Golf Associated produced universally growing seed (Brown, 2011). Now, grass is the number one irrigated crop (Greenspan, 2015) and forty million acres of lawn cover the United States, and up to ninety-five percent of the contiguous nation is developed (Baker, 2015; Garber, 2015).

-

Iverness Country Club in Toledo, Oklahoma, 1920. Iverness CC lays claim to the development of evergreen grass along with the Department of Agriculture.

But why do we devote such space to this useless design? To have all suburbs covered in grassy lawns, not devoted to any agricultural, wildlife, or ecological purpose means its purpose is solely culture. Manicured lawns, as much as they demonstrated elite aristocracy, now epitomize the American culture of “shared ideals, collective responsibility, [and] the assorted conveniences of conformity” (Garber, 2015). In fact, grandfather of American lawns Andrew Jackson Downing noted, “when smiling lawns and tasteful cottages begin to embellish a country, we know that order and culture are established” (Garber, 2015). This landscape is paramount to our “identity as Americans” (Pollan, 1989), and in our lawns are embedded even our most intimate social identities.

Disturbing this continuous expanse can be detrimental to neighborhood civility. Many sources cited Jay Gatsby’s overreaction to Nick Carraway’s overgrown grass, sending a groundskeeper to mow his neighbor’s lawn in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). But Gatsby’s breakdown is based in reality, and many struggle to not maintain their lawns (Baker, 2015; Greenspan, 2015). In many municipalities, “weed laws” – ordinances for short lawns – are enforced mainly to maintain property values (Kolbert, 2008), but also to coerce public order. Neighbors, communities, and municipalities actively impose uniform lawns. In fact, director of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, Paul Robbins, writes in Lawn People (2012 – a Temple University publication):

“The free-market American neoliberal subject who does as he or she pleases would just say, ‘To hell with my neighbors! I’m just going to let my lawn grow!’ But instead they do the Communist thing, which is collective management of what is essentially a moral commons. It’s not your lawn, it’s the whole community’s lawn, and you’re responsible for this part”

(Greenspan, 2015).

This is the inherent “contradiction of the American Dream: we want to stand out – but fit in” (Borelli, 2017). But when a plot does stand out, when it deviates from the norm, “where the shaved lawn rubs up against a shaggy one,” it is seen as “a scar on the face of suburbia” (Pollan, 1989). Roman Mars, creator of 99% Invisible, described uniform lawns as the “anti-broken window” (Garber, 2015) – manicured lawns each in turn promoting lawn maintenance. But lawns are completely purposeless and empty spaces. Professor of American Studies Elain Lewinnek of Cal State University in Berkeley, California, noted that “by the 1950s, [it was] firmly rooted that a front lawn is a painting, a non-productive space” (Borrelli, 2017); a painting to cover the nature surrounding our homes.

But just as lawns are useless, they are also harmful. Shaved lawns disrupt wildlife habitats, maintenance chemicals runoff into surrounding waterways, and a substantial amount of resources are utilized. As previously but briefly mentioned, the grass that now grows on American lawns never naturally grew in North America. Kentucky Bluegrass, Bermuda grass, and Zoysia grass are native to Europe and Northern Asia, Africa, and East Asia, respectively (Kolbert, 2008). Because growing this invasive species in dissimilar foreign climates depends “on the overcoming of local conditions” (Pollan, 1989), heavy maintenance is required to keep lawns green. In addition to producing universally viable grass, German chemist Fritz Haber, while developing weapon systems, synthesized ammonia: the “evergreen” fertilizer (Kolbert, 2008). In 1918, he won the Nobel Prize for his invention (“Fritz Haber – Biographical,” n.d.). Three decades later, at the height of World War II, American scientists synthesized a highly effective herbicide, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-d acid), which served a major component of carcinogenic Agent Orange (Kolbert, 2008). Both were eventually outlawed, but even the chemicals in use now can still contaminate waterways and entire ecosystems. These chemicals are extremely harmful to natural environments, wildlife habitats, and water sources. Additionally, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, the United States uses up to nine billion gallons of water per day to maintain green lawn cover (Garber, 2015). Nearly one-third of residential water is allocated to landscaping and lawn maintenance, as imported grasses require more water than natural rainfall provides (Garber, 2015; Kolbert, 2008). But it’s not just wasteful watering practices or detrimental chemicals that harm natural environments: mowing lawns contribute not only to resource consumption, it exacerbates large-scale environmental problems. Of the eight-hundred-plus million gallons of gasoline that Americans use annually for lawnmowers, seventeen million gallons are outright spilled, and the emissions from the clunky machines contribute to five percent of urban air pollution (Baker, 2015). Landscape architect Terry Ryan, of Jacobs/Ryan Associates, calls this “a poor use of resources” (Borrelli, 2017).

But “the urge to dominate nature is a deeply human one, and lawn mowing answers to it” (Pollan, 1989), and Americans do not seem to be pressed to change their lawn practices. Lawn mowing may be here to stay, but it may only inhibit healthy lawn environments. Trimmed grass is deprived of natural reproduction, an asexual process, and is stuck in a “perpetual state of vegetable adolescence;” this is simply “nature purged of sex and death” (Pollan, 1989). Leaving no inch to grow wildly nor reproduce, as a member of the English Parliament and agricultural writer William Cobbett once observed, lawns are “as barren as the sea beach” (Pollan, 1989). American lawns are void of any natural thicket, weed, or blossoming flower that makes nature, well, nature. Trimmed short, lawns cannot support wildlife, as migratory species need a “continuous habitat to thrive” (Baker, 2015). No weed, no bee, no possum live in the lawn. But the American lawn is “a symptom of, and a metaphor for, our skewed relationship to the land” (Pollan, 1989). In the eternal struggle of culture against nature, culture prevails via machines stifling the natural rejuvenating process. However, “if we allow ourselves to see a mowed lawn for what it is – a green desert that provides no food or shelter for wildlife – we can recondition ourselves to take pride in not mowing” (Baker, 2015).

This would be a push against more than a century of traditional, uniform lawns covering communities. Neighbors, like Jay Gatsby, would be discontent, but what is the United States without exceptional individualism? The lawn has transitioned from an elite commodity to an egalitarian and unifying staple of the American landscape, but unbounded egalitarianism has led to coerced conformity. This mindless conformity afforded to the landscape industry a mass market. Just over seventy-five percent of American homes have lawns that require maintenance (Brown, 2011). The amount that Americans spend on lawn care has declined over the past three decades, but still, upwards of $20 billion is spent annually (Garber, 2015; Kolbert, 2008; Pollan, 1989). Through matriculated ordinances and ostracizing communities, lawns are inexorably well-kept. Although the green expanse of lawns may seem egalitarian, the required maintenance depends on our continued subordination to the lawn industry, under the guise of our mastery of our home environment.

The domination of our environment comes with deserved retribution. Wildlife becomes scarce, resources are depleted, and individualism conforms. Is there something that the American citizen can do to resist this ecologically damaging, boring, and coerced habitat to which we have been committed? In this ubiquitous landscape, Bruce Butterfield of the National Garden Association poses the problem at hand:

“How do we approach this in a balanced way so our landscape looks good and is good for the plants and earthworms and animals and people? Because for many people in America, it’s not a choice whether they’re going to have a lawn, it’s ‘how are we going to manage it?’”

(Brown, 2011).

How indeed? Well, one could work to maintain their trimmed lawn, apply fertilizer for a vibrant green, perhaps all year long, and spend a fortune throughout their entire ownership of their yard. However, Steve Schneider of the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University notes, “When people think their lawns don’t look good, it’s often not because of grubs or insects or weeds, it’s because of poor watering and mowing practices. But people don’t realize this, and tend to water more and fertilize more” (Brown, 2011). But perhaps there is a better option, one where these empty shrines to conformity can have a purpose, grow wildly, and be sustainable.

The anti-lawn movement started in the cultural revolution of the 1960s and 70s. Rachel Carson’s 1962 manifesto Silent Spring and Lorrie Otto’s “Wild Ones” organization were some of the first to nationally denounce the purposelessness and harmfulness of lawns (Kolbert, 2008). In 1993, Yale University ecologists published Redesigning the American Lawn: A Search for Environmental Harmony. This book promoted, in lieu of expansive greenery, “freedom lawns” (Kolbert, 2008). Instead of boring, conforming lawns, “freedom lawns” are natural gardens, often with either tall grass or green cover that naturally grows shortly, like thyme, chamomile, and mint (Brown, 2011). Grass or green cover in its natural state requires less frequent watering and, if one were to mow, should do so infrequently and use a push lawnmower only. Most importantly, the cornerstone of freedom lawns is the rejection of chemical herbicides and pesticides (Kolbert, 2008). This practice allows for different plants, animals, and bugs to thrive, all part of a healthy ecosystem. Although overgrown grass and an abundance of pests may not seem aesthetically appealing, thriving freedom lawns are healthier than chemical-laden evergreen grass lawns.

-

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, 1962, one of the catalysts for the environmental movement

Freedom lawns provide a sustainable method of planning a beautiful and healthy residential environment. Instead of subordination, gardening is a “subtle process of give and take with a landscape, a search for some middle ground between culture and nature” (Pollan, 1989). No longer will grass sit idly on the lawn but will contribute to the newly-balanced ecosystem. Even local weeds will harbor wildlife such as pollenating bees. The new freedom lawns and gardens will “lessen our dependence on distant sources of energy, technology, food, and, for that matter, interest” (Pollan, 1989), and will drastically reduce the amount of resources the country as a whole consumes. But the implementation of freedom lawns and gardening on a large scale requires the radical rethinking of suburban conformity. With that comes confronting the “essential trouble with the American lawn… it is not a response to the landscape so much as an idea imposed upon it” (Kolbert, 2008). Therefore, in order to maintain healthy and sustainable lawns, “instead of putting nature in its place, we need to find our place in nature” (Baker, 2015).

-

Freedom lawns will set you free.

Outside my window, I look upon my neighbor’s backyard. She’s an old woman, and she and her grown daughter sit on the terrace. It’s a surprisingly big yard for an urban West Philadelphia house, and a path leads from the patio to a small patch of grass; a birdbath pond lies in the center. Large trees gently shade the two women as they sip lemonades, softly conversing with each other. Blossoming flora and large bushes surround their terrace, and their dog rolls around in the small patch of grass. Serenity is achieved. Their yard is organized and well-maintained, but it is how and what they maintain. No large expanse of grass, no need to fertilize. No use for a large mower. They have been sitting outside on their terrace for years. They have created a sustainable space in which they can consider and interact with nature, and be a part of their landscape and environment, not dominate it.

There are now multiple entities pushing lawn reformation. In line with the revolutionary concepts birthed out of the 1960s and 70s, states like California, Arizona, and Nevada – all arid regions, and compelled to act by drought – have actually paid their residents to get rid of their grassy lawns (Baker, 2015; Greenspan, 2015). Instead, local activists and institutions are promoting environment-friendly freedom gardens. Replacing grass with “soft, low-growing greenery” (Baker, 2011), like thyme and chamomile, will not only cut down on water usage, but will benefit all components of the suburban environment. Blossoming flowers within gardens will reintroduce pollenating bees and the rest of the ecosystem will follow. Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences published a guide (Brewer, 2014) on how to maintain a healthy and sustainable lawn. They suggest limiting watering and skipping chemical fertilizers, as well as other specific tips on creating a sustainable space. They are promoting freedom lawns. With activists and institutions endorsing these practices, we can enter into a new era of the suburban American lawn. Rather than pouring millions of dollars and resources into an elitist and purposeless outdoor space, we can put it, and ourselves, to good use. No longer will lawns sit vacant, unused yet over-manicured. No longer will we push out vital natural resources and wildlife, from forests to bees to weeds, and no longer will we depend so heavily on immoral chemical fertilizers that this industry has peddled so desperately. Instead, personal spaces will cover the suburban landscape, flowers will blossom, and our bountiful ecosystems will flourish. In gardening, intimacy abounds; “you not only see first-hand all the nature that we have lost start to come back, you get to interact with it” (Baker, 2015). In gardens comes real, personal freedoms. We can escape the conformity and harmfulness of popular short grass and find sustainable refuge in freedom lawns, and all it takes is understanding the natural features of our homes, and just a little bit of yardwork.

References

Baker, Sarah. (2015, August 3). “My township calls my lawn ‘a nuisance.’ But I still refuse to mow it.” Retrieved from The Washington Post website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/08/03/my-town-calls-my-lawn-a-nuisance-but-i-still-refuse-to-mow-it/?utm_term=.6ef0f2c11d89

Borrelli, Christopher. (2017, October 7). “How about rethinking a cultural icon? The front lawn.” Retrieved from The Chicago Tribune website: http://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/ct-ent-lawns-20171002-story.html

Brewer, Lori J. (2014). “Lawn care: The easiest steps to an attractive environmental asset.” Retrieved from Cornell University College of Agriculture & Life Sciences website: http://hort.cornell.edu/turf/lawn-care.pdf

Brown, Nell Porter (2011, March-April). “When grass isn’t greener.” Retrieved from Harvard Magazine website: https://harvardmagazine.com/2011/03/when-grass-isnt-greener

Duble, Richard L. (n.d.). “Buffalo grass.” Retrieved from Texas A&M Aggie Horticulture website: https://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/archives/parsons/turf/publications/buffalo.html

“Fritz Haber – biographical.” (n.d.). Retrieved from NobelPrize.org website: https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1918/haber-bio.html

Garber, Megan. (2015, August 28). “The life and death of the American lawn.” Retrieved from The Atlantic website: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/08/the-american-lawn-a-eulogy/402745/

Greenspan, Sam. (2015, August 8). “Lawn order.” Retrieved from 99% Invisible website: https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/lawn-order/

Hayden, Dolores. (2003). Building suburbia: green fields and urban growth 1820-2000. Vintage Books: New York City.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. (2008, July 21). “Turf war.” Retrieved from The New Yorker website: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/07/21/turf-war-elizabeth-kolbert

Pollan, Michael. (1989, May 28). “Why mow?; the case against lawns.” Retrieved from The New York Times Magazine website: https://www.nytimes.com/1989/05/28/magazine/why-mow-the-case-against-lawns.html?pagewanted=1

Further Reading

Food not lawns. (2017). http://www.foodnotlawns.com/

Ingraham, Christopher. (2015, August 4). “Lawns are a soul-crushing timesuck and most of us would be better off without them.” Retrieved from The Washington Post website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/08/04/lawns-are-a-soul-crushing-timesuck-and-most-of-us-would-be-better-off-without-them/?utm_term=.29b7ada8e9b7

Marohn, Charles. (2014, October 15). “The conservative case against the suburbs.” Retrieved from The American Conservative website: http://www.theamericanconservative.com/urbs/the-conservative-case-against-the-suburbs/

Pineo, Rebecca. (2010, March 10). “Turf grass madness: Reasons to reduce the lawn in your landscape.” Sustainable Landscape Series, 1(130), pp. 1-5.