The Holy Lamb in England

A New Critical Analysis of Religious Imagery in William Blake’s Jerusalem

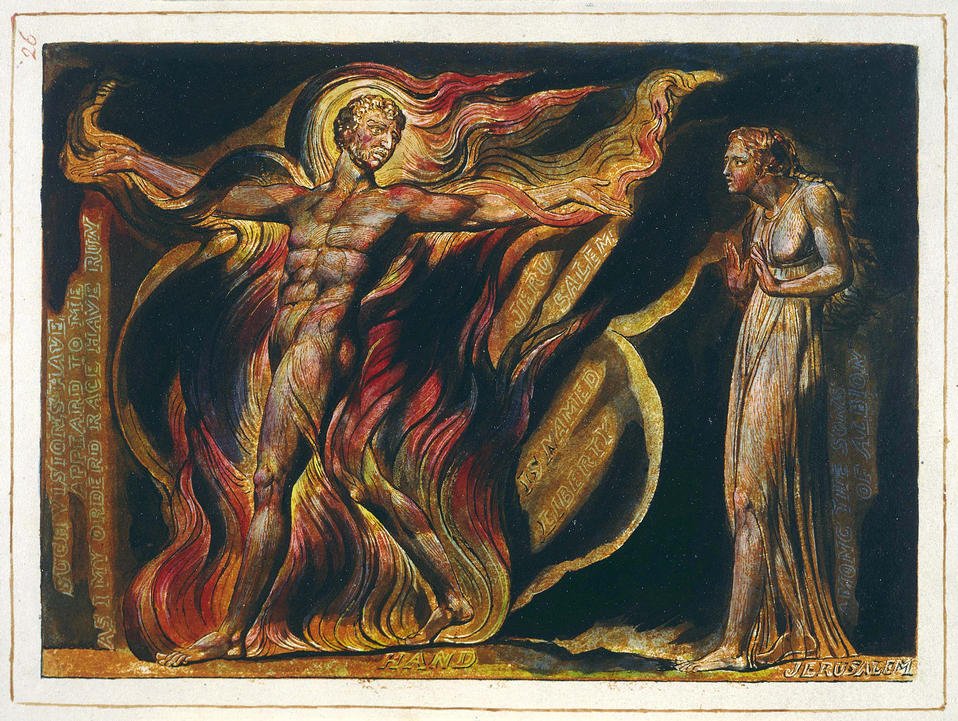

Feature photo from here

Originally submitted as part of the curriculum at Merrimack College | February 24, 2016

During the Middle Ages, stories of Jesus arriving in Britain during his Unknown Years started to arise, and some canonized the young Christ’s trip to the British Isles. According to the legend, Jesus and his great uncle, Joseph of Arimathea, established the second Christian church in England, the first being in Jerusalem (“Christ in Britain”). William Blake uses Christ arriving in Britain as the basis for his 1810 poem, “And did those feet in ancient time” (also known as the hymn “Jerusalem”). Blake fuses Christian tradition with Greek mythology, and uses this imagery to denounce the industrialization of Britain, as the nation stares down the Industrial Revolution. The 16-line poem packs a lot into the four stanzas of four. To start the poem, Blake presents a question: “And did those feet in ancient time / Walk upon Englands mountains green” (lines 1-2), which asks whether or not Jesus actually landed on the shores of the British coast. However, Blake does not ask how Jesus might have arrived if he had, but only if he had. This distinction is important, and it is the progressing idea of the poem. This is the start of the Christian imagery in the poem, and it continues throughout.

As Blake moves on to the next stanza, he talks of Britain, and this is where he turns his seemingly Christian poem into social commentary. The poem reads:

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic mills?

(lines 5-8).

Blake refers to the “pleasant prairies” (line 4) of England to be “clouded hills” (line 6), and this change in barometric amplitude shows a transition in Britain, which had just witnessed a fantastical renaissance and elegant royalties, but now stares down the barrel of machinery replacing humans and greed replacing happiness.

The language that Blake presents in this second stanza recalls upon the allegory he refers to in the first stanza: Jesus Christ arriving in England and establishing the second church, or, as Blake describes it, a “Countenance Divine” (line 5) shining across the country, essentially blessing the country and sanctifying it. The contradiction with the “dark Satanic mills” (line 8) again against the “pleasant pastures” (line 4) and, perhaps more importantly, the outright presence of God in the beginning of the second stanza slams the reader into the reality of what England had turned into: the First Industrial Revolution had left a cloud over England, although industry boomed, poverty ensued; while the economy skyrocketed, England suffered.

The new coal powered mills also left a smog over the country, like Neal Boenzi’s 1966 photograph “Smog,” picturing New York City from atop the Empire State Building on a particularly bad smog day (Boenzi). This smog, produced by the Industrial Revolution, led by greed and exploitation, prevented Christ’s divine light to shine down on the country: not only is there physical smog from the actual Industrial Revolution, but Blake insinuates that the entire basis of the Industrial Revolution is Satanic, casting a moral, religious, or supernatural smog over the country, preventing Christ’s touch to end the plagues of greed and poverty in Britain.

What divine being could touch upon a country of this caliber? This is what Blake is really asking in his social commentary. The first two stanzas of his poem paint a picture of a beautiful Britain (lines 1-4) and then immediately reverse the reader’s image of Britain to a “clouded” (line 6) and “Satanic” (line 8) country, physically and morally unable to be touched by the grace of God. The question that Blake proposes in the first two lines - whether or not Jesus stepped foot in England - can now be read as not whether he arrived, but as how could he have arrived? As stated previously, Blake does not mean, by which method did Jesus Christ make it to the Isles, but rather, in a hellish place, how could Christ be present? Blake is denouncing the current condition of Britain, a country once of beautiful pastures and mountains, but which is now one of smog and immoral industry. Certainly no divine Christ could be present with the condition that Britain was in, and Blake seemingly abandons the Christian allegory in the third stanza.

The third stanza turns from Christian allegory to Greek mythology, and in each of the four lines, Blake has similar commands. He writes,

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

(lines 9-12).

Blake references four distinct Greek myths: Apollo, Eros, Zeus, and Helios, respectively, and he relates each myth to anti-industrialization. Apollo was chosen for his golden burning bow. According to Greek myth, Apollo begged Hephaestus to give him the bow to protect Leto, Apollo’s mother, from Python. When Apollo got his bow, he killed Python in the sacred cave at Delphi (“Apollo’s Golden Bow”). In using Apollo’s story of his burning bow, Blake achieves multiple meanings: Blake compares the monster Python to the monster he sees in industrialization [the “Satanic mills” (line 8)], and he, acting as Apollo, kills the monster. Apollo’s bow is also extremely powerful. It could tear life away “like the harsh rays of the sun” (“Apollo’s Golden Bow”); Blake does not just want to kill the monster: he wants to absolutely destroy it, so there is no semblance of any physical mill, but also the ideology that caused the first establishment. Blake wants to completely destroy greed and exploitation that is tainting his beautiful Britain.

Eros was chosen perhaps for his Roman traditions: he symbolized life after death, and being a god of fertility (although he is most commonly known as the god of love) (Leadbetter), represented what Blake yearns to see in this rallying poem. After the demise of an attempt at industrialization, it will be destroyed and replaced with a fertile, green Britain, immortalized as Eros, the god with the “arrows of desire” (line 10).

Blake then asks for his spear, one that makes “clouds unfold” (line 11), which is a reference to Zeus’s bolts. After Zeus and the Olympians defeated the Titans, Gaea unleashed a monster, Typhoeus, after Zeus and his siblings. The king fled with his brothers and sisters, and Athena accused Zeus of cowardice, and he finally confronted Typhoeus. At first, Typhoeus defeated Zeus and took him to Python at Delphi (this source refers to Python as ‘Delphyne’ and the sacred cave at Delphi as its name, ‘Corycian Cave’), but Hermes was able to help Zeus escape on a chariot that rose up to the heavens. Finally, Zeus crushed Typhoeus underneath Mount Aetna, a volcano (“Zeus and His Fight with Typhon”). Using this myth, Blake wants Britons to end their cowardice and face the monster, industrialization. Although there was no specific reference to this myth in line 11, this absolutely has to be the one Blake references. Not only did Blake and Henry Fuseli create a divine engraving of this encounter (Blake and Fuseli), but the myth itself intertwined itself with Blake’s other references: the sacred cave at Delphi and Python from Apollo’s myth, and the chariot and Mount Aetna from Helios’.

Blake then moves on to asking for his “Chariot of fire” (line 12), a reference to Helios’ (although mostly Apollo’s) chariot that pulled the sun across the sky. According to myth, Phaeton, Helios’ son, tried to drive the chariot, but lost control and set the earth on fire (“Helios”). Blake included this line in reference to Helios, who is mainly known for just this story, because with the Industrial Revolution, humankind has effectively set the earth on fire, clouding over the mills and the once-peaceful pastures. This fire that humankind set is represented in the other Greek references: Apollo’s burning bow and Mount Aetna. Helios’ chariot is pulled by four horses, one of which is Aethon, meaning ‘burning’ or ‘blazing’ (“Aethon”).

Blake also reintroduces the Christian imagery in this line. In the Bible, after crossing the Jordan River, Elijah is brought up to Heaven by a whirlwind chariot of fire, and his successor, Elisha, is left with the spirit and burden of Elijah. Before Elijah’s departure, Elisha is asked on multiple occasions if he knows that his master will leave him on that day, and each time, Elisha responds that he will stay until his master is finally gone (New International Version Bible, 2 Kings 2 11-12). Blake knows that humankind has not stayed loyal, like Elisha had. By industrializing, humankind turned its back on the earth’s beautiful green mountains and “pleasant pastures” (line 4) and let it burn. The Romantic poet denounces the Industrial Revolution and prefers green to greed.

In fact, Blake does more than just denounce the industrialization of Britain: he vows to fight to completion, not with the Greek weaponry he armed himself with in the third stanza and in line 14, but also civilly and with intelligence and emotion. His “mental fight” (line 13) is a complete turnaround from his armament in the last stanza, but Blake knows that change must be weighed upon with great wisdom and a good vision.

William Blake’s vision, as made evidently clear in “And did those feet in ancient time,” is to rebuild Jerusalem in England. Perhaps it is not the New Jerusalem as described in the Book of Revelation, but it is certainly a yearning for some semblance of divinity or heaven among the hellish industrializing that Blake is seeing around him. In his 16-line poem, Blake denounces industrialization and how it is destroying his beautiful, natural Britain by using Christian and Greek imagery to question the morality of humankind as it faces a stage that will epitomize greed and everything that is exactly not Christian. By asking for his “Chariot of fire” (line 12), Blake is asking for Britain’s return to heaven, the nature and greenery of beautiful Britain.

Jerusalem, by William Blake

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon Englands mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

Works Cited

“Aethon.” Wikipedia. N.p., n.d. Web. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aethon

“Apollo’s Golden Bow.” Riordan Wiki. Wikia, n.d. Web. http://riordan.wikia.com/wiki/Apollo’s_Golden_Bow

Blake, William. “And did those feet in ancient time.” Poetry Foundation. 1810. Web. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/241908

Blake, William, and Henry Fuseli. Tornado. 1795. Engraving. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Boenzi, Neal. Smog. 1966. New York Times, New York City. New York Times Archive. Web.

“Christ in Britain.” Christ in Britain. N.p. 24 June 1997. Web. http://asis.com/users/stag/chrstbrt.html

“Helios.” Greek Mythology. N.p., n.d. Web. http://www.greekmythology.com/Other_Gods/Helios/helios.html

Leadbetter, Ron. “Eros.” Encyclopedia Mythica. N.p., 3 Mar. 1997. Web. http://www.pantheon.org/articles/e/eros.html

The New International Version Bible. “2 Kings 2: Elijah Taken Up to Heaven.” Bible Gateway. N.p., n.d. Web. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=2+Kings+2

“The Translation of Elijah: Part 1 (2 Kings 2:1-11).” Bible.org. N.p., n.d. Web. https://bible.org/seriespage/18-translation-elijah-part-1-2-kings-21-11

Whitcombe, Christopher L.C.E. “Delphi, Greece.” Sacred Places. Sweet Briar College, N.p., n.d. Web. http://whitcombe.sbc.edu/sacredplaces/delphi.html

“Zeus and His Fight with Typhon.” Greek Gods. N.p., n.d. Web. http://www.greek-gods.info/greek-gods/zeus/stories/zeus-typhoon/